“Nikkei in San Jose” is a blog series by volunteer and writer, Judith Ichisaka and published by JAMsj. Through research and interviews, Judith explores the diversity of the Japanese diaspora here within San Jose, both through a historical and personal lens. This article explores the experience of Japanese Americans in Hawai’i through Judith’s research and interview with JAMsj Board Member Aaron Ushiro.

Nikkei in San Jose: Japanese Peruvian

“Nikkei in San Jose” is a blog series by volunteer and writer, Judith Ichisaka and published by JAMsj. Through research and interviews, Judith explores the diversity of the Japanese diaspora here within San Jose, both through a historical and personal lens. This article explores the Japanese Peruvian experience through Judith’s research and interview with activist/community member Bekki Shibayama.

Nikkei in San Jose: Japanese Canadian

“Nikkei in San Jose” is a blog series by volunteer and writer, Judith Ichisaka and published by JAMsj. Through research and interviews, Judith explores the diversity of the Japanese diaspora here within San Jose, both through a historical and personal lens. This article explores the Japanese Canadian experience through Judith’s research and interview with San Jose Taiko’s Yurika Chiba.

Nikkei in San Jose: Meet Judith

“Nikkei in San Jose” is a blog series by volunteer and writer, Judith Ichisaka and published by JAMsj. Through research and interviews, Judith explores the diversity of the Japanese diaspora here within San Jose, both through a historical and personal lens. This article introduces Judith and her experiences that led to this project.

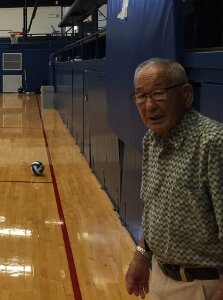

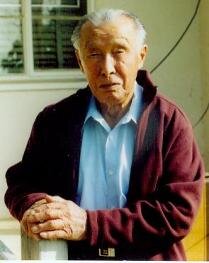

Remembering Jimi Yamaichi

Remembering Jimi YamaichiBy Will Kaku

The day after I heard that Jimi Yamaichi passed away, I didn't know what to do with myself. I felt a deep sorrow and emptiness. I viewed Jimi as a great mentor, a role model, an inspiration, and a friend. Although I did not sign up to be a docent at JAMsj on that day, I felt that it would be better for me if I came into the Museum that afternoon. I had hoped to find solace with others who knew Jimi, but I also desperately wanted to remain connected with Jimi's presence. Jimi put his entire heart and soul into the Museum and I can still feel his boundless energy, optimism, dreams, and passion in that space.Jimi's relentless drive and determination are well-known by those who know him. We all have our Jimi stories on this topic. I remember one time when we were working at the Museum construction site when I found him lying face down by the quonset huts. He insisted that he was fine and that he "would get up in a few minutes after resting." I performed a first-aid inspection on him and asked if he could feel me touching his arms and legs. He said that he didn't and I immediately called for an ambulance. This was just several days before he was to lead tours at the Tule Lake Pilgrimage. I called a friend of mine who was on the Pilgrimage planning committee and told her that Jimi would unfortunately not be attending because of his hospitalization. To my great surprise, Jimi still attended the event, leading tours and giving presentations with two black eyes!

Although I did not sign up to be a docent at JAMsj on that day, I felt that it would be better for me if I came into the Museum that afternoon. I had hoped to find solace with others who knew Jimi, but I also desperately wanted to remain connected with Jimi's presence. Jimi put his entire heart and soul into the Museum and I can still feel his boundless energy, optimism, dreams, and passion in that space.Jimi's relentless drive and determination are well-known by those who know him. We all have our Jimi stories on this topic. I remember one time when we were working at the Museum construction site when I found him lying face down by the quonset huts. He insisted that he was fine and that he "would get up in a few minutes after resting." I performed a first-aid inspection on him and asked if he could feel me touching his arms and legs. He said that he didn't and I immediately called for an ambulance. This was just several days before he was to lead tours at the Tule Lake Pilgrimage. I called a friend of mine who was on the Pilgrimage planning committee and told her that Jimi would unfortunately not be attending because of his hospitalization. To my great surprise, Jimi still attended the event, leading tours and giving presentations with two black eyes! Jimi was a very caring person. This is also true about his wife, Eiko, and the rest of the Yamaichi family. Since Jimi's passing, I have heard numerous stories about how Jimi and Eiko took people under their wing, especially those that lost loved ones or individuals who were new to the community.I remember when I first met Jimi at my first Tule Lake Pilgrimage. I was new in the community and I didn't know anybody as I sat by myself in the auditorium. Jimi came by and sat next to me. He immediately struck up a conversation and gave me some historical items that he had collected. Jimi made me feel very special. Jimi did that with everyone.

Jimi was a very caring person. This is also true about his wife, Eiko, and the rest of the Yamaichi family. Since Jimi's passing, I have heard numerous stories about how Jimi and Eiko took people under their wing, especially those that lost loved ones or individuals who were new to the community.I remember when I first met Jimi at my first Tule Lake Pilgrimage. I was new in the community and I didn't know anybody as I sat by myself in the auditorium. Jimi came by and sat next to me. He immediately struck up a conversation and gave me some historical items that he had collected. Jimi made me feel very special. Jimi did that with everyone. I asked Jimi many questions about the Tule Lake concentration camp, the "No-No Boys", renunciation, resistance, and dissent in the camps. Those are difficult issues that I still struggle with today. My family's past actions do not fall into the overpowering, inspirational, and often repeated narrative of Japanese Americans who overcame their unjust incarceration through their great military valor, heroism, and patriotism. I had nobody who could explain at a deeply personal level why someone would take these controversial positions as my relatives were deceased, suffering from dementia, or were extremely reticent to talk about their past actions.Jimi understood my conflict. He thoughtfully explained to me the tortuous personal journey that he took in protesting his confinement. To my surprise, he later told me that he stood with my uncle in a Eureka courtroom where the Tule Lake resisters told the judge their side of the story. Through these conversations with Jimi, I began to understand that Jimi, my family and other dissidents did not hate this country and were not cowards, as some have called them. They simply wanted this country to uphold its very values, beliefs, and laws under the Constitution.

I asked Jimi many questions about the Tule Lake concentration camp, the "No-No Boys", renunciation, resistance, and dissent in the camps. Those are difficult issues that I still struggle with today. My family's past actions do not fall into the overpowering, inspirational, and often repeated narrative of Japanese Americans who overcame their unjust incarceration through their great military valor, heroism, and patriotism. I had nobody who could explain at a deeply personal level why someone would take these controversial positions as my relatives were deceased, suffering from dementia, or were extremely reticent to talk about their past actions.Jimi understood my conflict. He thoughtfully explained to me the tortuous personal journey that he took in protesting his confinement. To my surprise, he later told me that he stood with my uncle in a Eureka courtroom where the Tule Lake resisters told the judge their side of the story. Through these conversations with Jimi, I began to understand that Jimi, my family and other dissidents did not hate this country and were not cowards, as some have called them. They simply wanted this country to uphold its very values, beliefs, and laws under the Constitution. One of my last memories of Jimi was at this year's Day of Remembrance program, an event that I help organize every year. I came to his home the day before the event to pick up the beautiful candle lighting display that he created for the ceremony that honors Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II. Jimi had just come home from the hospital after an illness. I told him that it would be better if he didn't come to the event so he could fully recuperate. The next evening, I was shocked to see Jimi at the event. Somehow he willed his frail body to attend the program. His son, George, told me that Jimi felt that the event was very important to him and he insisted that George drive him to the event. I realize how physically strenuous it was for Jimi to make -- what I now know-- his final trip to the event. That really means a lot to me.

One of my last memories of Jimi was at this year's Day of Remembrance program, an event that I help organize every year. I came to his home the day before the event to pick up the beautiful candle lighting display that he created for the ceremony that honors Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II. Jimi had just come home from the hospital after an illness. I told him that it would be better if he didn't come to the event so he could fully recuperate. The next evening, I was shocked to see Jimi at the event. Somehow he willed his frail body to attend the program. His son, George, told me that Jimi felt that the event was very important to him and he insisted that George drive him to the event. I realize how physically strenuous it was for Jimi to make -- what I now know-- his final trip to the event. That really means a lot to me. On the day after his passing, it was somewhat difficult for me to give museum tours that day since I always have several Jimi stories that I incorporate into my narrative. I had to pause or slow down a bit after I became a bit emotional. I still get teary-eyed as I tell those stories but I also know that Jimi's spirit, vision, and dreams live on here at the Museum, in San Jose Japantown, at Tule Lake, and most importantly, within all of us.

On the day after his passing, it was somewhat difficult for me to give museum tours that day since I always have several Jimi stories that I incorporate into my narrative. I had to pause or slow down a bit after I became a bit emotional. I still get teary-eyed as I tell those stories but I also know that Jimi's spirit, vision, and dreams live on here at the Museum, in San Jose Japantown, at Tule Lake, and most importantly, within all of us.

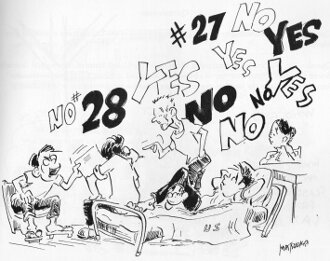

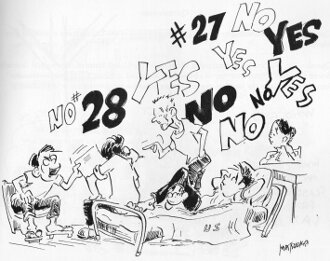

Return to Heart Mountain

By Will KakuThe Heart Mountain concentration camp has always represented a critical turning point for my father’s family. As I had written in previous articles and speeches (links to some of these are below), Heart Mountain was the place where my father and his brothers struggled and debated as to how they were going to answer the infamous Questions 27 and 28. Heart Mountain was the location where my Uncle Tak decided that he was going to resist the draft. Heart Mountain was where my Aunt Itsu made a dramatic transformation from an innocent, acquiescent, and naive young women to one who became more aware of her dire situation and more vocal about racial discrimination and the violation of her civil rights.

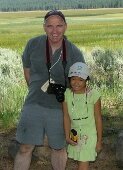

By Will KakuThe Heart Mountain concentration camp has always represented a critical turning point for my father’s family. As I had written in previous articles and speeches (links to some of these are below), Heart Mountain was the place where my father and his brothers struggled and debated as to how they were going to answer the infamous Questions 27 and 28. Heart Mountain was the location where my Uncle Tak decided that he was going to resist the draft. Heart Mountain was where my Aunt Itsu made a dramatic transformation from an innocent, acquiescent, and naive young women to one who became more aware of her dire situation and more vocal about racial discrimination and the violation of her civil rights. Despite that significance in my family’s history, I could never find the time to make the journey to the Heart Mountain Interpretative Center. During the fall, my mother told me she wanted to visit Yellowstone National Park, so I decided that I could finally combine that trip with a visit to the old camp site which is just an hour drive from the park.

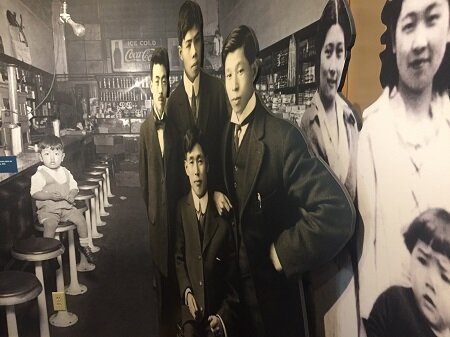

Despite that significance in my family’s history, I could never find the time to make the journey to the Heart Mountain Interpretative Center. During the fall, my mother told me she wanted to visit Yellowstone National Park, so I decided that I could finally combine that trip with a visit to the old camp site which is just an hour drive from the park. The Heart Mountain Interpretative Center opened in 2011, just a year after we completed the major renovation of JAMsj. Because I assisted in providing content for the JAMsj camp exhibit, I was fully aware of space, cost, and vision constraints that had to be considered in exhibit design. I was keenly interested in how the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation (HWMF) presented the Japanese American incarceration story to the public in their facility.

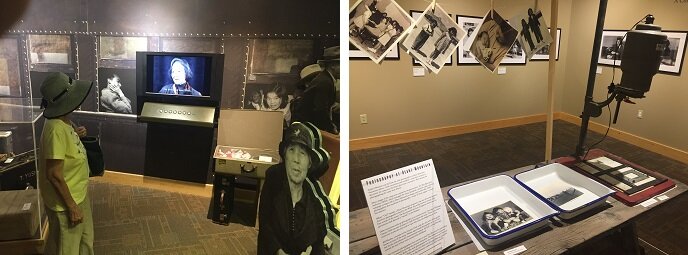

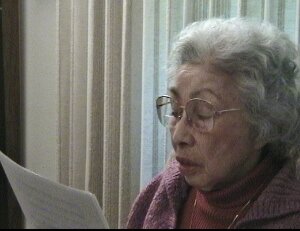

The Heart Mountain Interpretative Center opened in 2011, just a year after we completed the major renovation of JAMsj. Because I assisted in providing content for the JAMsj camp exhibit, I was fully aware of space, cost, and vision constraints that had to be considered in exhibit design. I was keenly interested in how the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation (HWMF) presented the Japanese American incarceration story to the public in their facility. One major aspect of the HWMF presentation, the first-person narrative, is extremely effective in bringing out an emotional connection to an infamous event in our nation’s history from over 75 years ago. After a short museum overview, my mom and I were encouraged to view the short film, All We Could Carry, by Oscar-winning filmmaker, Steven Okazaki. All We Could Carry powerfully captures the devastating impact of incarceration at Heart Mountain through the voices of former inmates.

One major aspect of the HWMF presentation, the first-person narrative, is extremely effective in bringing out an emotional connection to an infamous event in our nation’s history from over 75 years ago. After a short museum overview, my mom and I were encouraged to view the short film, All We Could Carry, by Oscar-winning filmmaker, Steven Okazaki. All We Could Carry powerfully captures the devastating impact of incarceration at Heart Mountain through the voices of former inmates.

Several kiosks in the museum also incorporate moving first-person accounts. Exhibit placards continuously reinforce the first-person point of view by utilizing the inclusive pronoun "we". We felt that we were also making our own journey through the great civil liberties and human rights tragedy from WW II.

Several kiosks in the museum also incorporate moving first-person accounts. Exhibit placards continuously reinforce the first-person point of view by utilizing the inclusive pronoun "we". We felt that we were also making our own journey through the great civil liberties and human rights tragedy from WW II. The 11,000 square feet of space also enables exhibit images and artifacts to extend out into the floor space, providing a fully immersive experience to the visitor.

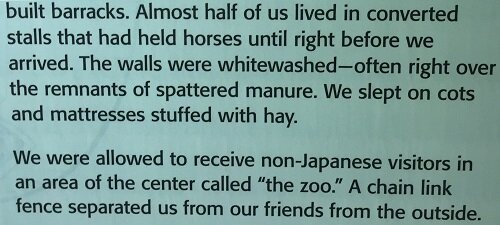

The 11,000 square feet of space also enables exhibit images and artifacts to extend out into the floor space, providing a fully immersive experience to the visitor. Every square foot of the museum is used to transport you back into the diverse and complex Japanese American incarceration experience. Even the reflective restroom toilet stalls convey the feeling of embarrassment and the loss of privacy that many former inmates experienced in the camps.

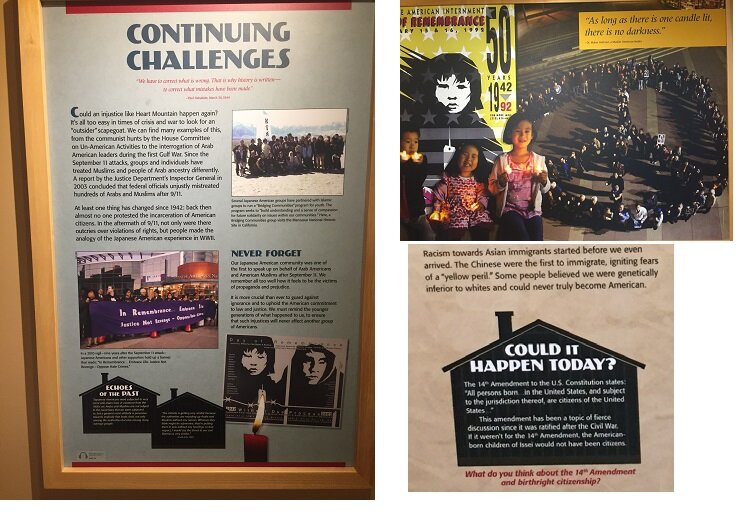

Every square foot of the museum is used to transport you back into the diverse and complex Japanese American incarceration experience. Even the reflective restroom toilet stalls convey the feeling of embarrassment and the loss of privacy that many former inmates experienced in the camps. Importantly, the museum exhibits challenge visitors with questions that are pertinent to our lives and political discourse today. One display asks us about what we think about the 14th Amendment and birthright citizenship. Another asks us if there are any circumstances under which the curtailment of civil liberties by the government is justified.

Importantly, the museum exhibits challenge visitors with questions that are pertinent to our lives and political discourse today. One display asks us about what we think about the 14th Amendment and birthright citizenship. Another asks us if there are any circumstances under which the curtailment of civil liberties by the government is justified. It took us a long time to explore the many museum displays and my mother became tired. We came back the next morning and wandered around the self-guided walking tour next to the museum. We saw the locations of the Heart Mountain hospital where my father worked for a short time, the school that he attended, and the train station where my father boarded a train that transferred him to the Tule Lake camp. We walked solemnly during that quiet, cool morning and we reflected on his life.

It took us a long time to explore the many museum displays and my mother became tired. We came back the next morning and wandered around the self-guided walking tour next to the museum. We saw the locations of the Heart Mountain hospital where my father worked for a short time, the school that he attended, and the train station where my father boarded a train that transferred him to the Tule Lake camp. We walked solemnly during that quiet, cool morning and we reflected on his life.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Related articles by Will Kaku:Lost WordsThe Secret of Tule LakeLiving HistoryPower of Words: Internment Camp or Concentration Camp

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Related articles by Will Kaku:Lost WordsThe Secret of Tule LakeLiving HistoryPower of Words: Internment Camp or Concentration Camp

The Importance of Japanese American Traditions

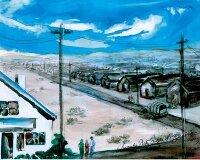

By Susan NakamuraOne of the goals of the Japanese American Museum of San Jose (JAMsj) is to preserve the unique history of our ancestors for future generations and to share their accomplishments and hardships with others. Japanese Americans can trace their roots to Japan. But their immigration to America, farming experience, and incarceration during World War II have combined to create Japanese American identity and culture.As a young girl, I recall my mother pointing out my grandfather as an example of gaman: persevering through difficult times with hard work and without complaining. Through his example I should learn these virtues. Because my grandfather was born in Oahu, Hawaii, at that time a U.S. territory, he was a dual citizen of the United States and Japan. The family came stateside in 1906, the year of the San Francisco earthquake. They were forced to move every four years because the California Alien Land Law of 1913 prohibited Japanese from owning land or possessing leases for more than three years.My grandmother was a picture bride from Kumamoto, a province on the island of Kyushu in Japan. Initially, my grandmother and her father were reluctant to have her travel to a ‘foreign’ country and unknown land. Her father later changed his mind. He told my grandmother that if she went to America and married my grandfather, they would return to Japan in three years. As it turned out, they never returned to Japan.My Grandmother Kajiu changed her name to Yoso, because Kajiu was also the name of my grandfather’s mother. And two Kajius in America would be too confusing. She took the name Yoso, her older sister’s name, who died earlier from a brain hemorrhage after working in the rice fields.According to papers, my grandparents were married in 1919, but my grandmother did not make her journey to America until 1920. She sailed out of the port of Nagasaki on the SS Persia Maru, the last ship for picture brides from Japan. The journey to California took 27 days, with a stop in Hawaii to let off other picture brides.Like many Japanese immigrants in Santa Clara valley, they worked as farmers. They grew strawberries and vegetables in Sunnyvale, San Jose, and Campbell while they raised their growing family. In about 1940, the family of seven children moved back to Campbell, where they lived in a tar-paper house with an outdoor furo (bath) and latrine (outhouse). The location of the property was on Union Avenue, not too far from the Pruneyard shopping center, which at that time was a prune orchard.During WWII, the family was incarcerated in the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming. The family members traveled there by train with the blinds drawn down; they were not allowed to look out the window. Then they were transported in military trucks to the barracks. They saw their first snow ever, and to these Californians it was very cold. Their barracks had a pot belly coal stove in the middle and army cots for beds. The mess hall, bathroom, and washroom were in another building. There were blizzards in the winter and thunderstorms in the summer.After the war ended in 1945, my grandparents’ family members returned to Campbell. They were fortunate that their landlord, Mr. Whipple, had watched their house and belongings. But they had to start from scratch to get on their feet and earn a living. They picked prunes, prunes, and more prunes, because it was a family job, one in which everyone worked together. Later they became sharecroppers, growing strawberries with other white farmers.Growing up in Santa Clara Valley, our extended family traditions included mochitsuki, obon, and hinamatsuri. It is amazing that these traditions could survive through all the hardships of life in America.At JAMsj, these traditions are being carried forward so that future generations and the community can learn about their roots or the roots of their friends. Strong personal virtues and a sense of one’s roots can help develop your own identity and define who you are. And that is why we at JAMsj feel it is important to have programs and events to celebrate, commemorate, and uphold these traditions.For more information about internment camps and to view a replica of a camp barrack, visit JAMsj at 535 North Fifth Street in San Jose. Completely run and operated by community volunteers, JAMsj is open from Thursday through Sunday, 12 noon to 4 p.m. The admission fee is $5 for adults; $3 for seniors and students; and free to members, children under 12, and active military. We would love to see you.Please join JAMsj on March 1 for our annual hinamatsuri festivities. Children and their parents will be able to create items with paper, glue, and other crafting supplies. Hinamatsuri activities are fun, social, and open to the public. Adult helpers will be on hand to supervise these fun art activities.(I credit my aunt, June Takata, who was the unofficial family historian, for the many details included here. I also picked prunes.)

Lost Words

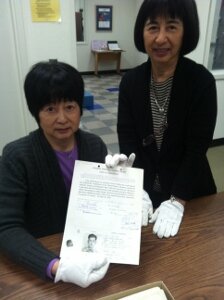

The following year-end essay is written by Will Kaku, a JAMsj board member and an organizer for the San Jose Day of Remembrance program.By Will KakuIt has been said by many that writing letters is a lost art form. People under the age of 35 or so may have never experienced the sentimental emotions of discovering that dusty old shoebox full of beautifully crafted letters that convey love, joy, sorrow, and introspection. The grief-stricken letter with tear-stained handwriting or the scented love letter expressing longing and passion cannot compare to a laboriously long email thread or be reduced to a 140-character tweet with an embedded emoticon. I recently had a remarkable shoebox moment when I came across several wartime letters written by my aunt, Itsuyo Kaku Hori (or “Aunt Its” as we called her) while she was incarcerated in the Santa Anita Assembly Center and the concentration camp in Heart Mountain, Wyoming . The letters were unknown to me until UC Davis professor Cecilia Tsu visited JAMsj and, by chance, informed me that she had discovered the letters when she was performing research at the History San Jose archives. The letters were sent to Elizabeth Wade, who was the friendly and caring landlord of the San Jose property where my aunt and her family farmed before the war.Those personal letters, as well as other wartime correspondence and documentation that I have collected, challenge us with the concept of what it really means to be an American. The letters also dramatically reveal a tumultuous period that propelled my young aunt into an incredible emotional journey and a great personal transformation.

I recently had a remarkable shoebox moment when I came across several wartime letters written by my aunt, Itsuyo Kaku Hori (or “Aunt Its” as we called her) while she was incarcerated in the Santa Anita Assembly Center and the concentration camp in Heart Mountain, Wyoming . The letters were unknown to me until UC Davis professor Cecilia Tsu visited JAMsj and, by chance, informed me that she had discovered the letters when she was performing research at the History San Jose archives. The letters were sent to Elizabeth Wade, who was the friendly and caring landlord of the San Jose property where my aunt and her family farmed before the war.Those personal letters, as well as other wartime correspondence and documentation that I have collected, challenge us with the concept of what it really means to be an American. The letters also dramatically reveal a tumultuous period that propelled my young aunt into an incredible emotional journey and a great personal transformation. The first letters that she wrote from Santa Anita captured my 19-year-old aunt’s youthful innocence, optimism, trust, and naiveté. She mentioned the arduous, seventeen-hour train ride from San Jose to Santa Anita, how she missed the ranch in San Jose, and the long lines of people waiting for their camp meals. But she also remarked that Santa Anita is “a nice place” and that ”the race track is beautifully built with a large grandstand.”“There are millions of people from all directions,” Aunt Its wrote. She was awestruck. “For you know that this is our first experience to see such a big place with so many people, that it will be a great, big adventure to us. We don’t know how long the government is going to keep us here, but we are well satisfied. It’s amazing to see what the government can do for so many people at this and the other camps.”

The first letters that she wrote from Santa Anita captured my 19-year-old aunt’s youthful innocence, optimism, trust, and naiveté. She mentioned the arduous, seventeen-hour train ride from San Jose to Santa Anita, how she missed the ranch in San Jose, and the long lines of people waiting for their camp meals. But she also remarked that Santa Anita is “a nice place” and that ”the race track is beautifully built with a large grandstand.”“There are millions of people from all directions,” Aunt Its wrote. She was awestruck. “For you know that this is our first experience to see such a big place with so many people, that it will be a great, big adventure to us. We don’t know how long the government is going to keep us here, but we are well satisfied. It’s amazing to see what the government can do for so many people at this and the other camps.” Aunt Its wrote to Elizabeth Wade every two months. And she continued to write the “newsy” letters, as she referred to them, after the family was transferred to the Heart Mountain concentration camp. She wrote cheerfully, “This is our first experience in snow and it looks so pretty and white. The children seem to enjoy themselves by playing snow fights and making a snowman.” Coincidentally, she mentioned that she saw “the young Mr. Sakauye every time I go to the post office.” (I wasn’t aware that she knew JAMsj founder, Eiichi Sakauye).These later letters from Heart Mountain also conveyed the first depictions of hardship. She remarked that the cold weather “affects the old folks very much, especially our Mom. She says that she feels as though her ear has been taken off. We all wish this war would be over pretty soon, but I guess it’s for the time to decide it. Let us all wish for the best of things now.”Strangely, the continuous stream of letters comes to an abrupt halt in March 1943. I’m not sure why, but this is the same month the family requested repatriation to Japan (the request was rescinded a few months later). In addition, it was around the time that the highly controversial “loyalty questionnaire” was issued at Heart Mountain.

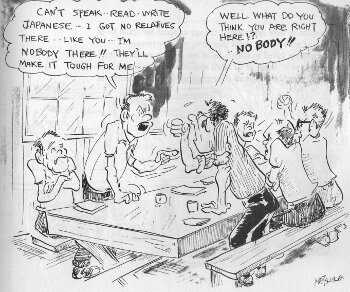

Aunt Its wrote to Elizabeth Wade every two months. And she continued to write the “newsy” letters, as she referred to them, after the family was transferred to the Heart Mountain concentration camp. She wrote cheerfully, “This is our first experience in snow and it looks so pretty and white. The children seem to enjoy themselves by playing snow fights and making a snowman.” Coincidentally, she mentioned that she saw “the young Mr. Sakauye every time I go to the post office.” (I wasn’t aware that she knew JAMsj founder, Eiichi Sakauye).These later letters from Heart Mountain also conveyed the first depictions of hardship. She remarked that the cold weather “affects the old folks very much, especially our Mom. She says that she feels as though her ear has been taken off. We all wish this war would be over pretty soon, but I guess it’s for the time to decide it. Let us all wish for the best of things now.”Strangely, the continuous stream of letters comes to an abrupt halt in March 1943. I’m not sure why, but this is the same month the family requested repatriation to Japan (the request was rescinded a few months later). In addition, it was around the time that the highly controversial “loyalty questionnaire” was issued at Heart Mountain. My father recounted to me many years ago when he was still lucid that the camp became a highly volatile place during that period. He recalled that there were people who applied great pressure on him to take a stand one way or another on the questionnaire. He remembered that whenever he had a meal in the mess hall, there was always somebody on the other side of the table emphatically demanding that he answer the questionnaire according to their strongly held point of view.Perhaps because my Issei grandfather wanted the family to repatriate to Japan, his children who were old enough to sign the questionnaire did not answer the controversial questions #27 and #28 in the affirmative. Although government records show that my father argued with his father because he wanted to stay in America and that he subsequently registered for Selective Service, he did not answer the questions, which was considered the same as giving a negative response. He was thus labeled as a disloyal “No-No Boy."

My father recounted to me many years ago when he was still lucid that the camp became a highly volatile place during that period. He recalled that there were people who applied great pressure on him to take a stand one way or another on the questionnaire. He remembered that whenever he had a meal in the mess hall, there was always somebody on the other side of the table emphatically demanding that he answer the questionnaire according to their strongly held point of view.Perhaps because my Issei grandfather wanted the family to repatriate to Japan, his children who were old enough to sign the questionnaire did not answer the controversial questions #27 and #28 in the affirmative. Although government records show that my father argued with his father because he wanted to stay in America and that he subsequently registered for Selective Service, he did not answer the questions, which was considered the same as giving a negative response. He was thus labeled as a disloyal “No-No Boy." Most people who answered "no-no" to questions #27 and #28 were moved to the Tule Lake Segregation Center, a high security camp in California near the Oregon border. The results of the questionnaire eventually separated my aunt from the rest of her family. After getting married, my Aunt Its decided to stay in Heart Mountain while the rest of the family was sent to the Tule Lake.Transcripts of my aunt’s leave clearance hearings reveals a young woman who was undergoing a radical transformation in her thinking. Her husband failed to report to his draft induction, demanding that he would serve in the armed forces only if his rights were fully restored. My uncle is subsequently arrested and sent away to a Department of Justice camp and then later to Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary. My aunt is left alone in Heat Mountain, separated from her husband and her family. Her earlier feelings of optimism, trust, and hope are now replaced by confusion and cynicism.

Most people who answered "no-no" to questions #27 and #28 were moved to the Tule Lake Segregation Center, a high security camp in California near the Oregon border. The results of the questionnaire eventually separated my aunt from the rest of her family. After getting married, my Aunt Its decided to stay in Heart Mountain while the rest of the family was sent to the Tule Lake.Transcripts of my aunt’s leave clearance hearings reveals a young woman who was undergoing a radical transformation in her thinking. Her husband failed to report to his draft induction, demanding that he would serve in the armed forces only if his rights were fully restored. My uncle is subsequently arrested and sent away to a Department of Justice camp and then later to Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary. My aunt is left alone in Heat Mountain, separated from her husband and her family. Her earlier feelings of optimism, trust, and hope are now replaced by confusion and cynicism.

| Anderson (Assistant Project Director): | How has all this made you feel toward the United States? |

| Hori (my aunt): | Before evacuation, it was swell, it was all right, just like other people. I felt good, but since being put in camp, it is something different. |

| Anderson: | As far as the future is concerned, do you feel that you could live your life here and be satisfied that you are an American? |

| Hori: | It is hard to tell right now. |

| Anderson: | You may feel that as a citizen you haven’t been treated right, but there is no question about your being a citizen. You are. Do I understand that the thing that you object to, you disagree with, is the fact you have been evacuated and have been required to live in a relocation center? |

| Hori: | Yes. As citizens we should be treated like other Americans. |

| Anderson: | You still think that under these conditions, you could be a sincerely loyal American, or do you feel that would make you feel a little bitter toward this country? |

| Hori: | (No reply) |

Assistant Project Director Anderson continued to press the argument that it is a citizen’s responsibility to report for military service even though he or she is forced into a “relocation center” and that the two issues are separate and should not be confused.

| Anderson: | Why do you think that you and your husband are any different than myself in regard to such an obligation? You think that I should go, but you feel you and your husband are justified in not going (to join the army). |

| Hori: | They should give us some of the rights back to us, and then it is all right for us to go. |

| Anderson: | What rights? |

| Hori: | Rights of the citizen. Free to go out like other Americans before evacuation. They shouldn’t force us into relocation centers. |

Several members of the Leave Clearance Review Committee debated whether my aunt was truly a loyal American. One member wrote his review with underlined annotations for emphasis, “There are no indications of disloyalty, but rather a misconception of evacuation and Selective Service which has not been cleared up. If her husband and she are willing to suffer because of what they think American rights are, both would fight if they were given an understanding of the total picture.”What they think? When I read this handwritten notation, I am amazed that people cannot see within themselves their own misconception about what American rights are.My aunt stayed in Heart Mountain, separated from her husband and her family in Tule Lake. When she found out her father was dying, she had to obtain permission to visit him. Aunt Its told me once about the multiday train ride from Heart Mountain to Tule Lake. “The train was full of soldiers and nobody would give me a seat. Finally, one Japanese American soldier gave me a seat.” When she arrived at Tule Lake, the camp authorities recorded her fingerprints and took several mug shots. “ We were discriminated against. We were Japs,” Aunt Its said.

Several members of the Leave Clearance Review Committee debated whether my aunt was truly a loyal American. One member wrote his review with underlined annotations for emphasis, “There are no indications of disloyalty, but rather a misconception of evacuation and Selective Service which has not been cleared up. If her husband and she are willing to suffer because of what they think American rights are, both would fight if they were given an understanding of the total picture.”What they think? When I read this handwritten notation, I am amazed that people cannot see within themselves their own misconception about what American rights are.My aunt stayed in Heart Mountain, separated from her husband and her family in Tule Lake. When she found out her father was dying, she had to obtain permission to visit him. Aunt Its told me once about the multiday train ride from Heart Mountain to Tule Lake. “The train was full of soldiers and nobody would give me a seat. Finally, one Japanese American soldier gave me a seat.” When she arrived at Tule Lake, the camp authorities recorded her fingerprints and took several mug shots. “ We were discriminated against. We were Japs,” Aunt Its said. There was another handwritten letter from my aunt in the government’s archives that stirs sadness within me. In her letter, my aunt emotionally pleaded with a government official to let her stay at the Tule Lake camp so that she could take care of her ailing father.“When I met him, I was so shocked to see him completely changed from the time we separated last,” my aunt wrote in her letter to the project director. “That really was terrible for me to bear. I feel so sorry for my mother, watching her care for my father and children also. It makes me feel that I want to stay here forever and help, but I’m afraid that is impossible. I do not know when I will meet them (the family) again, and probably by then, he’ll pass away.”

There was another handwritten letter from my aunt in the government’s archives that stirs sadness within me. In her letter, my aunt emotionally pleaded with a government official to let her stay at the Tule Lake camp so that she could take care of her ailing father.“When I met him, I was so shocked to see him completely changed from the time we separated last,” my aunt wrote in her letter to the project director. “That really was terrible for me to bear. I feel so sorry for my mother, watching her care for my father and children also. It makes me feel that I want to stay here forever and help, but I’m afraid that is impossible. I do not know when I will meet them (the family) again, and probably by then, he’ll pass away.” My aunt was eventually given permission to stay at Tule Lake. She took care of her father until he died several weeks after the war ended.I was lucky to interview my Aunt Its before she passed away in 2007. Her controversial stories cover a topic that has been very difficult and painful for the Japanese American community. But, the stories also strike at the heart of the definitions of American identity, loyalty, equality, and justice. They have inspired me to ensure that her story, as well as the stories from others, are kept alive at JAMsj.In my eulogy to her, I said that my aunt took me on a wonderful journey, resulting in my coming out as a different person on the other side. Discovering these previously unknown letters let me travel on that remarkable journey with her one more time. I hope that one day you will also find the “lost words” of a loved one so that you can embark on a similar journey.------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Contact: will@jamsj.orgLinks:To request "WWII Japanese American Internment and Relocation Records" from the National Archives: http://www.archives.gov/research/japanese-americans/San Jose Day of Remembrance: http://www.sjnoc.org/

My aunt was eventually given permission to stay at Tule Lake. She took care of her father until he died several weeks after the war ended.I was lucky to interview my Aunt Its before she passed away in 2007. Her controversial stories cover a topic that has been very difficult and painful for the Japanese American community. But, the stories also strike at the heart of the definitions of American identity, loyalty, equality, and justice. They have inspired me to ensure that her story, as well as the stories from others, are kept alive at JAMsj.In my eulogy to her, I said that my aunt took me on a wonderful journey, resulting in my coming out as a different person on the other side. Discovering these previously unknown letters let me travel on that remarkable journey with her one more time. I hope that one day you will also find the “lost words” of a loved one so that you can embark on a similar journey.------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Contact: will@jamsj.orgLinks:To request "WWII Japanese American Internment and Relocation Records" from the National Archives: http://www.archives.gov/research/japanese-americans/San Jose Day of Remembrance: http://www.sjnoc.org/ The Day of Remembrance commemorates the anniversary of Executive Order 9066 which led to the forced incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese descent, two-thirds of whom were American citizens. Each year, we gather to remember that great civil liberties tragedy from over seventy years ago and each one of us reflects on what that event means to us today.The Day of Remembrance is an event that aims to bring different communities together in order to build trust, respect and understanding among all people and to renew our pledge to fight for equality, justice and peace.Other articles by Will Kaku:The Secret of Tule LakeLiving HistoryAn American Time CapsuleThe Echoes of E.O. 9066The Emotional Journey Into Camp Days

The Day of Remembrance commemorates the anniversary of Executive Order 9066 which led to the forced incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese descent, two-thirds of whom were American citizens. Each year, we gather to remember that great civil liberties tragedy from over seventy years ago and each one of us reflects on what that event means to us today.The Day of Remembrance is an event that aims to bring different communities together in order to build trust, respect and understanding among all people and to renew our pledge to fight for equality, justice and peace.Other articles by Will Kaku:The Secret of Tule LakeLiving HistoryAn American Time CapsuleThe Echoes of E.O. 9066The Emotional Journey Into Camp Days

Q&A with Common Ground Exhibit Curators, Connie Young Yu and Leslie Masunaga

Connie Young Yu and Leslie Masunaga are JAMsj guest curators. They are currently working on the new JAMsj exhibit, "Common Ground: Chinatown and Japantown, San Jose," which will open in September of 2012. They sat down with interviewer, Nancy Yang, to discuss their vision for the exhibit.What inspired you to create this exhibit? Was there anything in your own life experience that drove you to create the exhibit? Connie: I grew up hearing about my parents and their oral history. My father was born on Cleveland Avenue (in Heinlenville, which no longer exists. Heinlenville was a Chinatown that would be located within the boundaries of present day San Jose Japantown). He was in his twenties when he left the 6th street settlement. My father was actually there until 1937. So his memories were very strong.He remembered Japantown and having Japanese neighbors. He saw the transformation from Chinatown to Japantown. This is what I think is really exciting. I feel that this site of Cleveland Avenue, of Sixth Street, and Jackson Street was the birthplace of the first Asian American community in Santa Clara Valley. It was no longer just Chinatown, and no longer just Japantown. More Asians moved in including Filipinos. This was really the first multicultural place.I think that the story (about Chinatown and Japantown) is very inspiring. You want to reach people in a way that they can understand and identify with, because the story is ultimately about people, and it’s about conflict and struggle.It’s important to realize that Chinatown and Japantown existed because of immigration restrictions. In 1972, I wrote this article called “Remembering 1882.” It was about the Chinese Exclusion Act, and there was a lot of research into the anti-Asian laws. There’s a lot of history and background to this site, which still survives as Japantown, and the roots of that were in the Anti-Asian Laws.There was a fence that was built when Chinatown was new (an eight-foot high fence that was covered with barbed wire originally surrounded Heinlenville). The fence was locked up every night by Charlie (community leaders hired Charlie, a white security guard who patrolled the area). Gradually, there was no fear of people who could come and burn another Chinatown down. The fence was to protect the Chinese, he said, so no one could get in, and no one could get out.Leslie: Basically, I was into the historic preservation of buildings, because they were tearing down all of downtown San Jose. And the building I was in, they tore up under it, so I got into history and got into general local history.The community doesn’t know its history. The individual histories aren’t there, much less the history of Japantown, Northside, and other neighborhoods. While we start developing things, everything gets wiped out. And people keep saying that San Jose has no soul and I say that’s because we keep erasing things. You don’t celebrate. You don’t build on something. You just keep wiping it out, and then it begins to look like everything else.The sad thing about San Jose is that just about all of the Chinese experience has disappeared. There are a lot of Chinese in the Valley, but there’s no particular Chinese place. There’s no town. There’s not even an event center.Now that these communities like Japantown are over 100 years old, it’s important to maintain what’s there. We want the community to prosper, but we also want to celebrate and commemorate the past and what’s there.That’s great that you have those anecdotes about the interaction between the Japanese and the Chinese communities.Connie: These were Asian American activities, but the cultures of China and Japan are so different, and a perfect example is the theater. Chinese theater is so elaborate and Japanese theater is very different. The Japanese had sumo wrestling, which the Chinese did not. There is an anecdote from a woman that I interviewed. She remembered that her mother said, “there’s a half naked man down the street!” It was a sumo wrestler doing an exhibition. They were very shocked because the Chinese never dressed like that.Leslie: This area was the center of the shopping, and the social life, and everything else. Even though all the Asians farmed, they would come here to do the shopping, to go to church, to do things, and some of it’s really interesting is to see where that interplay is. One of the things in the exhibit is a check that my grandfather wrote, but it’s made out to the Tek Wo board. Obviously they were trading with each other and they were buying from different stores, but they were very distinct communities. The interaction wasn’t necessarily at the personal level; it was not necessarily that people would go to the same churches, or the same social clubs, but there was this community interplay. Dr. Ishikawa (Dr. Tokio Ishikawa formerly owned the property where JAMsj currently resides) talks about buying lottery tickets from the Chinese that were around. And Grant Elementary School (near Japantown) was a mixed school. You can see the pictures.Why do you think that there is not a greater general awareness of early Chinatowns and Japantowns and how they have contributed to the present day?Leslie: The problem with history in schools, is that they try and cram in the big picture, the mainstream idea, and it tends to be East Coast dominated.Everybody hears about Ellis Island, but nobody hears really about Angel Island. Even teachers don’t know. They may know that these (Asian) people came in the 1850’s and that the Chinese worked on the railroads, but that’s it.The problem is, Connie’s book really is about the only book out there that’s about Chinatown in San Jose. So you don’t get the whole picture, you get one little story and then you have to go look for it. We just don’t have a mechanism where people are learning the history.Connie: I always go back to the Chinese Exclusion Act. When you exclude a people, there’s a disconnect. Their immigration is interrupted. And when it’s interrupted, it becomes a blank story.After the exclusion law was repealed, people had a hard time talking about the past. The exclusion law separated families and excluded Asians from American society. When you’re excluded, you don’t write about it. You have no record, you are invisible. You’re not a citizen – you’re just a non-entity.From 1882 to 1943, laborers were excluded and their history was obliterated. Most history is written from the point of the victors – the businesses, or the leaders. The laborers are omitted.And you know what happened - that’s why all the Chinatowns faded. It was a cultural center, and it was a home base for agricultural workers. So you have Chinese workers, and then Japanese, and then after when the Japanese were excluded and persecuted, you have the Mexicans, and then the Filipinos. There are people who specialize in labor history, and there are books on labor, but who would want to write about labor, except people who really were affected by it.

Connie Young Yu and Leslie Masunaga are JAMsj guest curators. They are currently working on the new JAMsj exhibit, "Common Ground: Chinatown and Japantown, San Jose," which will open in September of 2012. They sat down with interviewer, Nancy Yang, to discuss their vision for the exhibit.What inspired you to create this exhibit? Was there anything in your own life experience that drove you to create the exhibit? Connie: I grew up hearing about my parents and their oral history. My father was born on Cleveland Avenue (in Heinlenville, which no longer exists. Heinlenville was a Chinatown that would be located within the boundaries of present day San Jose Japantown). He was in his twenties when he left the 6th street settlement. My father was actually there until 1937. So his memories were very strong.He remembered Japantown and having Japanese neighbors. He saw the transformation from Chinatown to Japantown. This is what I think is really exciting. I feel that this site of Cleveland Avenue, of Sixth Street, and Jackson Street was the birthplace of the first Asian American community in Santa Clara Valley. It was no longer just Chinatown, and no longer just Japantown. More Asians moved in including Filipinos. This was really the first multicultural place.I think that the story (about Chinatown and Japantown) is very inspiring. You want to reach people in a way that they can understand and identify with, because the story is ultimately about people, and it’s about conflict and struggle.It’s important to realize that Chinatown and Japantown existed because of immigration restrictions. In 1972, I wrote this article called “Remembering 1882.” It was about the Chinese Exclusion Act, and there was a lot of research into the anti-Asian laws. There’s a lot of history and background to this site, which still survives as Japantown, and the roots of that were in the Anti-Asian Laws.There was a fence that was built when Chinatown was new (an eight-foot high fence that was covered with barbed wire originally surrounded Heinlenville). The fence was locked up every night by Charlie (community leaders hired Charlie, a white security guard who patrolled the area). Gradually, there was no fear of people who could come and burn another Chinatown down. The fence was to protect the Chinese, he said, so no one could get in, and no one could get out.Leslie: Basically, I was into the historic preservation of buildings, because they were tearing down all of downtown San Jose. And the building I was in, they tore up under it, so I got into history and got into general local history.The community doesn’t know its history. The individual histories aren’t there, much less the history of Japantown, Northside, and other neighborhoods. While we start developing things, everything gets wiped out. And people keep saying that San Jose has no soul and I say that’s because we keep erasing things. You don’t celebrate. You don’t build on something. You just keep wiping it out, and then it begins to look like everything else.The sad thing about San Jose is that just about all of the Chinese experience has disappeared. There are a lot of Chinese in the Valley, but there’s no particular Chinese place. There’s no town. There’s not even an event center.Now that these communities like Japantown are over 100 years old, it’s important to maintain what’s there. We want the community to prosper, but we also want to celebrate and commemorate the past and what’s there.That’s great that you have those anecdotes about the interaction between the Japanese and the Chinese communities.Connie: These were Asian American activities, but the cultures of China and Japan are so different, and a perfect example is the theater. Chinese theater is so elaborate and Japanese theater is very different. The Japanese had sumo wrestling, which the Chinese did not. There is an anecdote from a woman that I interviewed. She remembered that her mother said, “there’s a half naked man down the street!” It was a sumo wrestler doing an exhibition. They were very shocked because the Chinese never dressed like that.Leslie: This area was the center of the shopping, and the social life, and everything else. Even though all the Asians farmed, they would come here to do the shopping, to go to church, to do things, and some of it’s really interesting is to see where that interplay is. One of the things in the exhibit is a check that my grandfather wrote, but it’s made out to the Tek Wo board. Obviously they were trading with each other and they were buying from different stores, but they were very distinct communities. The interaction wasn’t necessarily at the personal level; it was not necessarily that people would go to the same churches, or the same social clubs, but there was this community interplay. Dr. Ishikawa (Dr. Tokio Ishikawa formerly owned the property where JAMsj currently resides) talks about buying lottery tickets from the Chinese that were around. And Grant Elementary School (near Japantown) was a mixed school. You can see the pictures.Why do you think that there is not a greater general awareness of early Chinatowns and Japantowns and how they have contributed to the present day?Leslie: The problem with history in schools, is that they try and cram in the big picture, the mainstream idea, and it tends to be East Coast dominated.Everybody hears about Ellis Island, but nobody hears really about Angel Island. Even teachers don’t know. They may know that these (Asian) people came in the 1850’s and that the Chinese worked on the railroads, but that’s it.The problem is, Connie’s book really is about the only book out there that’s about Chinatown in San Jose. So you don’t get the whole picture, you get one little story and then you have to go look for it. We just don’t have a mechanism where people are learning the history.Connie: I always go back to the Chinese Exclusion Act. When you exclude a people, there’s a disconnect. Their immigration is interrupted. And when it’s interrupted, it becomes a blank story.After the exclusion law was repealed, people had a hard time talking about the past. The exclusion law separated families and excluded Asians from American society. When you’re excluded, you don’t write about it. You have no record, you are invisible. You’re not a citizen – you’re just a non-entity.From 1882 to 1943, laborers were excluded and their history was obliterated. Most history is written from the point of the victors – the businesses, or the leaders. The laborers are omitted.And you know what happened - that’s why all the Chinatowns faded. It was a cultural center, and it was a home base for agricultural workers. So you have Chinese workers, and then Japanese, and then after when the Japanese were excluded and persecuted, you have the Mexicans, and then the Filipinos. There are people who specialize in labor history, and there are books on labor, but who would want to write about labor, except people who really were affected by it.

Heinlenville Exhibit Opens in September 2012

By Nancy Yang

This September, guest curators Connie Young Yu and Leslie Masunaga will unveil a special exhibit, "Common Ground: Chinatown and Japantown, San Jose," at JAMsj that focuses on the story of Heinlenville, San Jose’s last Chinatown. Yu is the author of Chinatown, San Jose, USA, now in its fourth edition. The new JAMsj exhibit will focus on the personal story behind Heinlenville’s residents and chronicle that community’s relationship to and influence on current-day Japantown.The exhibit will feature artifacts from a 2008 Sonoma State University archaeological excavation of the Heinlenville site. Included in the collection are personal mementos of the curators, including a check made out by Masunaga’s grandfather to the Tuck Wo store, and objects from Yu’s family. There will also be a video associated with the exhibit that incorporates photos and interviews.The construction of San Jose’s last Chinatown began in 1887, several months after arson destroyed the Market Street Chinatown. Heinlenville was bordered by Fifth, Seventh, Jackson, and Taylor streets. It was established at a time of great anti-Asian sentiment, amid calls by city leaders and citizens for the complete elimination of Chinese settlements within the city’s perimeters. Heinlenville was originally surrounded by an eight-foot high fence covered with barbed wire to protect the Chinese from anti-Chinese elements.The namesake of the town is John Heinlen, a German American immigrant and businessman who defied convention in the 1880s by agreeing to lease land to the Chinese and Japanese in San Jose. His defiant actions, made during a time when strong nativist passions were also rampant, still resonate with us today.“I feel San Jose should feel very proud,” Yu said. “Having someone like John Heinlen made a huge difference. If it weren’t for him, I think that we (San Jose) would probably have a very bleak racial image. He’s the greatest example of somebody doing good for the community and rising above (the racial turmoil). I feel that if we do anything, it’s to keep the history, the memory, and the inspiration of John Heinlen alive.”A shared emphasis of their past projects was a focus on community education, through both open houses and public outreach. Yu recalls, “For two years in a row, Leslie and I did our own exhibit. We just put up picnic tables. We had the artifacts and memorabilia, and people could come by and take a look.”“There’s something tangible, in having something to touch and see,” says Masunaga about the artifacts. “It’s something that connects to you as opposed to seeing something in a book, or on paper, or something that just becomes very academic and very cold.” Tangible items, such as boar’s teeth, marbles, and jade bracelets, in conjunction with photographs and anecdotes, help to elucidate the daily life of Heinlenville. This combination also illuminates the quiet dignity of citizens, in the face of outside hostility.This personal approach to history is echoed in the Heinlenville exhibit, as the curators’ vision is to celebrate the colorful life and history of Chinatown and its relationship to present-day Japantown. “I think this is an opportunity to say that this place existed, in terms of a physical community,” says Masunaga. “We want to really bring that aspect forward and give more depth to the community that’s here today--not just to the Japanese American community, but also to the local scene--and to understand the interplay between the communities.”Masunaga notes the significance of telling the Chinese American story. “The sad thing about San Jose is that just about all of the Chinese experience has disappeared. There are a lot of Chinese in the Valley, but there’s no particular Chinese place. There’s no town. There’s not even an event center."Yu reflects on the deeper meaning of the exhibit, “It’s really an all-American story. They’d always say, ‘that’s your history,’ or they’d call it ethnic history. But I would say no. I’m talking about American history. And when Leslie talks about local history, she’s talking about our roots. It’s not strictly Asian American history, and it is not a story about ‘you guys.’”Both curators have deep roots in the Bay Area and have worked extensively together as a team. The two first met in 1990 when Masunaga was working as an archivist at the San Jose Historical Museum, and Yu was working on the book, Chinatown, San Jose, USA.

Juri Kameda Conquers All Odds and Lives Life to the Fullest

On Saturday, April 14, Juri Kameda jumped out of a plane to raise awareness and money and for the ALS Therapy Development Institute. Juri is a friend of JAMsj and her beautiful jewelry is sold in the museum's store. JAMsj President Aggie Idemoto interviewed Juri before her jump.

Juri Kameda Conquers All Odds and Lives Life to the Fullest

By Aggie Idemoto

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6jzYYeOMzIs]

Japan-born Juri Kameda immigrated to the U.S. and her life has since been one of transitions. Her most recent career change as a jeweler connected her to JAMsj.

Juri attended Japanese and Catholic schools in Japan until the fifth grade, when she transitioned to an American education. This change meant a shift in educational methodology and expectations, as well as languages. Juri is fluent in Japanese, English, Spanish and has a conversational grasp of Mandarin. With her diverse language skills, she aspired to work with the United Nations, but her parents steered her toward a career in medicine or technology. “There’s no money working for a non-profit,” they cautioned.After studying at Foothill Community College and U.C. San Diego with a major in cognitive science, Juri began her career as a certified respiratory care practitioner. She then moved into the technology world as a simultaneous translator. When her 2-year-old son started violin lessons and needed larger violins as he grew up, Juri began to make his violins herself. These experiences lead to her position with the Kamimoto String Instruments shop in Japantown, making and repairing violins and cellos.In her spare time, Juri plays the flute, and for the past ten years has been an avid abalone diver. She and her husband, Ken, are world travelers, making one major trip every two years.In 2005, she experienced the biggest transition of her life when she was diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease. This neurological disease causes muscle weakness, disability, and eventually death. There is no known cure. The news struck a devastating blow, but did not crimp any plans for Juri.During a trip to Helsinki three years ago, she discovered and was enthralled by a unique form of glass jewelry, which instantly inspired her to go into the making of glass jewelry. Her disability requires the assistance of a wheel chair, respirator, and service dog, but Juri has use of three fingers in both hands and puts her creative outlet, energy, and vitality for living into each of her hand-crafted creations. A jeweler for over a year, her creations are featured in the JAMsj store. She contributes 5% of her proceeds to ALS Guardian Angels.When asked what message she wants to shout out to others, she did not hesitate with the following: “Live life like there’s no tomorrow. Live for the moment and don’t dwell on the unknown.” Juri Kameda is a truly inspiring role model for all of us.On Saturday, Juri Kameda and her friend, Gloria Hale, a San Jose resident who is also diagnosed with ALS, made the jump to raise awareness for the disease. To make a donation in support of Juri Kameda , Gloria Hale, and the ALS Therapy Development Institute, go to http://community.als.net/skydiveforYFALS.

A jeweler for over a year, her creations are featured in the JAMsj store. She contributes 5% of her proceeds to ALS Guardian Angels.When asked what message she wants to shout out to others, she did not hesitate with the following: “Live life like there’s no tomorrow. Live for the moment and don’t dwell on the unknown.” Juri Kameda is a truly inspiring role model for all of us.On Saturday, Juri Kameda and her friend, Gloria Hale, a San Jose resident who is also diagnosed with ALS, made the jump to raise awareness for the disease. To make a donation in support of Juri Kameda , Gloria Hale, and the ALS Therapy Development Institute, go to http://community.als.net/skydiveforYFALS.

Anniversary of infamy for American freedoms

Local journalist and writer Marty Cheek has been a friend of JAMsj for many years. Marty wrote the following article on the 70th anniversary of Executive Order 9066. This article was originally published in the Gilroy Dispatch on February 24, 2012.By Marty CheekLast Sunday marked an anniversary of infamy for American freedom.That sunny day in the South Valley marked 70 years since President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave the U.S. military broad powers to force 120,000 American citizens to leave their homes and possessions to be relocated behind the barbed-wire fences of concentration camps in desolate locations. I consider Roosevelt's decision on Feb. 19, 1942 to sign Executive Order 9066 one of the most atrocious failings by a U.S. president in upholding America's traditions of freedom and democracy. Many argued then - as some argue now - that the president was required to place American citizens of Japanese ancestry in internment camps during World War II as a national defense measure. Roosevelt defended his decision by saying the "successful prosecution of the war requires every possible protection against espionage." Refuting that argument is the fact that there was never one proven case of a Japanese-American citizen during the war participating in an action of sabotage, espionage or otherwise assisting the enemy. Considering the evidence that has emerged in recent decades, the true reason for the "evacuation" of Japanese-American citizens was racism and a desire by some to suppress economic competition.Not long after the evacuation started, and many of these citizens, including families in the South Valley region, were rounded up and taken to assembly centers. A music teacher in California's San Joaquin Valley wrote these words as part of a three-page statement he presented to U.S. Army officers at a hearing at the Presidio military base in San Francisco:"True democracy, while recognizing the right of the majority to rule, is also unique in the position established by the fathers of this country in recognizing the rights of the minority. That is the reason why the really democratic form of government is superior to all others. Democracy recognizes the right of the individual to freedom of conscience and religious worship. That right must be carefully guarded by all Christians and believers in true democracy. The spirit of democracy in this respect must not be destroyed in times of national stress or emergency. It is far too valuable to be lost by the efforts of those who have forgotten the real value of life."I happened to come across the document containing those words while going through a box of old papers. The irony struck me that I found the testimony the day before the 70th anniversary of President Roosevelt's signing of Executive Order 9066. The document had a double impact on me because I am reading the book "The Muslim Next Door: The Qur'an, the Media, and that Veil Thing" by Sumbul Ali-Karamali. As an event for the Silicon Valley Reads program, I'll conduct a public discussion of the book at the Morgan Hill Library on March 10.Sept. 11 is my generation's Pearl Harbor. The surprise attack by terrorists 10 years ago and its aftermath has parallels with the Japanese military's strike on the U.S. Navy base in Honolulu and the hysteria that spawned injustice for Japanese Americans. As part of the aftermath of Sept. 11, our nation is dealing with religious prejudice toward Muslim Americans. This prejudice has prompted some politicians to stir up the hysteria of 9/11 and promote legally sanctioned discrimination, in the form of anti-Sharia laws, against those who follow the faith of Islam.Political representatives in more than a dozen states have worked on legislation to outlaw traditional Islamic laws in the United States. Congresswoman Michele Bachmann has advocated the suppression of Islamic religious law, stating that the intention of Muslims is to "usurp" the U.S. Constitution with Sharia. And Republican presidential candidate Newt Gingrich has told supporters "Sharia is a mortal threat to the survival of freedom in the United States and in the world and we know it."Let me tell you about that teacher who wrote the statement for the U.S. Army hearing. He was a proud Republican because he believed that his political party exemplified the legacy of Lincoln, a legacy of liberty. That man was my father, Raymond Cheek. By the end of 1942, my dad would go to the Tule Lake Internment Camp in a high desert valley near the California-Oregon border to teach music to young Japanese-American children behind barbed-wire fences because they were considered enemies of the United States.America is an exceptional nation. In our past, we have risen above our racial and religious bigotries. To uphold our traditions of freedom and democracy, we must remember to do so again.-------------------------------------------------------------------------------Marty Cheek is a journalist who resides in the city of Morgan Hill. His father Raymond Cheek taught music at the Tule Lake Internment Camp. He can be reached at martin.cheek@gmail.com

Many argued then - as some argue now - that the president was required to place American citizens of Japanese ancestry in internment camps during World War II as a national defense measure. Roosevelt defended his decision by saying the "successful prosecution of the war requires every possible protection against espionage." Refuting that argument is the fact that there was never one proven case of a Japanese-American citizen during the war participating in an action of sabotage, espionage or otherwise assisting the enemy. Considering the evidence that has emerged in recent decades, the true reason for the "evacuation" of Japanese-American citizens was racism and a desire by some to suppress economic competition.Not long after the evacuation started, and many of these citizens, including families in the South Valley region, were rounded up and taken to assembly centers. A music teacher in California's San Joaquin Valley wrote these words as part of a three-page statement he presented to U.S. Army officers at a hearing at the Presidio military base in San Francisco:"True democracy, while recognizing the right of the majority to rule, is also unique in the position established by the fathers of this country in recognizing the rights of the minority. That is the reason why the really democratic form of government is superior to all others. Democracy recognizes the right of the individual to freedom of conscience and religious worship. That right must be carefully guarded by all Christians and believers in true democracy. The spirit of democracy in this respect must not be destroyed in times of national stress or emergency. It is far too valuable to be lost by the efforts of those who have forgotten the real value of life."I happened to come across the document containing those words while going through a box of old papers. The irony struck me that I found the testimony the day before the 70th anniversary of President Roosevelt's signing of Executive Order 9066. The document had a double impact on me because I am reading the book "The Muslim Next Door: The Qur'an, the Media, and that Veil Thing" by Sumbul Ali-Karamali. As an event for the Silicon Valley Reads program, I'll conduct a public discussion of the book at the Morgan Hill Library on March 10.Sept. 11 is my generation's Pearl Harbor. The surprise attack by terrorists 10 years ago and its aftermath has parallels with the Japanese military's strike on the U.S. Navy base in Honolulu and the hysteria that spawned injustice for Japanese Americans. As part of the aftermath of Sept. 11, our nation is dealing with religious prejudice toward Muslim Americans. This prejudice has prompted some politicians to stir up the hysteria of 9/11 and promote legally sanctioned discrimination, in the form of anti-Sharia laws, against those who follow the faith of Islam.Political representatives in more than a dozen states have worked on legislation to outlaw traditional Islamic laws in the United States. Congresswoman Michele Bachmann has advocated the suppression of Islamic religious law, stating that the intention of Muslims is to "usurp" the U.S. Constitution with Sharia. And Republican presidential candidate Newt Gingrich has told supporters "Sharia is a mortal threat to the survival of freedom in the United States and in the world and we know it."Let me tell you about that teacher who wrote the statement for the U.S. Army hearing. He was a proud Republican because he believed that his political party exemplified the legacy of Lincoln, a legacy of liberty. That man was my father, Raymond Cheek. By the end of 1942, my dad would go to the Tule Lake Internment Camp in a high desert valley near the California-Oregon border to teach music to young Japanese-American children behind barbed-wire fences because they were considered enemies of the United States.America is an exceptional nation. In our past, we have risen above our racial and religious bigotries. To uphold our traditions of freedom and democracy, we must remember to do so again.-------------------------------------------------------------------------------Marty Cheek is a journalist who resides in the city of Morgan Hill. His father Raymond Cheek taught music at the Tule Lake Internment Camp. He can be reached at martin.cheek@gmail.com

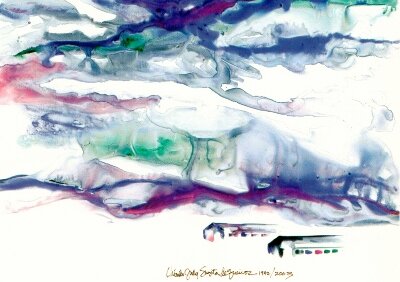

The Emotional Journey into Camp Days

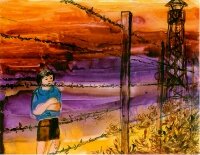

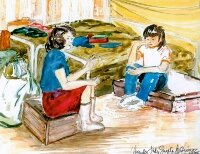

The following article was written by JAMsj docent, Will Kaku. He reflects on the Chizuko Judy Sugita de Queiroz’ Camp Days 1942-1945 exhibit. The exhibit will be closing on December 30, 2011.

The Emotional Journey into Camp Days

By Will Kaku

When the JAMsj reopened in October 2010, I used to start my tours like many docents do: in chronological order starting with the story of Chinese and Japanese immigration, the insatiable appetite for cheap labor by agribusiness and industrialists, the impact of racial attitudes and anti-Asian exclusionary laws, and the transition of an immigrant population from a “bachelor society” to one of permanence in San Jose’s Japantown. To me, to start from the beginning was the only way to tell this story.That is how many of us learned history in school. We were often immersed in historical timelines, the identification of key events, influential innovations, political leaders and movements, and the study of causality. There were many facts that had to be understood, necessitating a firm grasp on the “who, what, why, when, and where” of history.When it came to Chizuko Judy Sugita de Quieroz’ watercolor art exhibit, Camp Days 1942-1945, it just didn’t seem to fit my linearly constructed, fact-driven narrative. I often concluded my tours informing my tour group that we also had an art exhibit room which they could walk through and enjoy at their own leisure.I just didn’t get it. I simply saw that there were brightly colored images on the exhibit walls that depicted slices of camp life. There didn’t seem to be any sense of connectivity and profundity, and it missed the opportunity to make an overt political statement. There were also several paintings done in a child-like manner. I could probably paint better than that, I thought.During my breaks, I used to sit and relax in the Camp Days exhibit room, enjoying quiet, introspective times. Letting my mind wander into Chizuko’s paintings, I would reflect on the many former internees that I had met. And eventually, I started to understand.Sometimes the appreciation of art is like that. Like a fine wine, you often can’t appreciate it until you are fully aware of its subtle complexity. You cannot viscerally connect to the work until you are able to unlock the deeply embedded emotional layers. Chizuko’s exhibit describes a young girl’s journey into womanhood and reveals a deeply personal, emotionally scarring reaction to internment, a reaction that many former internees can identify with. For many in the Japanese American community, the repercussions of internment define who we are, shaping our values, political beliefs, and emotional character.In Chizuko’s work, there are basically two major styles represented in the exhibit: a representational form and an abstract form that embeds impressionistic components. Many of the representational forms are painted in a child-like manner, although it would be more accurate to say that they are painted through the eyes of a young Chizuko and layered with the knowledge of what was yet to come from the adult Chizuko.Chizuko had the most difficult time trying to create the abstract forms. Many of these paintings are heavily textured with deep emotions that include sorrow, loneliness, loss, and longing.