Last month, my family braved the blazing hot 100+ degree weather and journeyed on a road trip to Oregon. As we neared the state border, we made a special detour about an hour east of Highway 5 to visit the Tule Lake National Monument, located near the small town of Newell, California. Tule Lake is significant to my husband’s family because his grandparents and great-grandparents on both sides were wrongfully incarcerated there during World War II, along with more than 18,700 other Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens. We had never taken our child there, so it would be an important educational experience for him.

The new visitor center at Tule Lake National Monument.

More than 10 years ago, my husband and I went to Tule Lake and were disappointed to find only two small acknowledgements of the site’s wartime history: a dusty roadside sign and a very small display in the nearby Lava Beds National Monument Visitor Center. So when we visited last month, we were happy to discover that the National Park Service had opened a new visitor center in June, and we had arrived just in time to join a tour of the jail constructed by none other than Japanese American Museum of San Jose co-founder Jimi Yamaichi.

Inside the Tule Lake Internment Camp Jail

Tule Lake was the largest of the 10 WWII camps run by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), and it was also the only one with a jail. This was because Tule Lake was a maximum security site that incarcerated Japanese Americans who answered “no - no” to two notorious survey questions intended to identify potential enemies. In reality, the survey questions were so poorly worded that many Japanese Americans answered “no - no” out of confusion, suspicion or other reasons.

After the park ranger unlocked the gate, and we drove towards the historic wartime jail, it was truly dramatic to see the lone building in a vast, dusty field, with craggy mountain bluffs looming in the background. Our park ranger led us through various rooms of the jail and told many stories about its history, including how Yamaichi, a master carpenter, initially refused the WRA’s request to oversee the jail’s construction, but later relented when told the WRA would just find someone else. As foreman, Yamaichi tried to delay construction of the jail as much as possible, demanding the highest-grade construction materials, which were difficult to come by. While the barracks, guard towers, and other buildings were dismantled and removed after the war , it is because the jail was so well built with such sturdy materials that it still stands today.

The historic jail at the Tule Lake incarceration camp.

Another story our park ranger told was about Mrs. Osborne, a local woman who worked in the camps, and how she had the foresight to purchase several of the steel doors and jail beds when the camp closed. She asked her family to safeguard them as historical artifacts, and in 2012, more than 70 years later, one of her relatives donated them to the National Park Service. Thanks to the dedication of the Osborne family, visitors can see several of the original cell doors and beds installed in the jail today.

The most memorable part of the jail was seeing graffiti written on walls next to cell beds, which gives you a sense of the sadness and desperation that prisoners felt. One person inscribed, “SHOW ME THE WAY TO GO HOME.” Another person wrote in elegant cursive script, “When the golden sun has sunk beyond the desert horizon, and darkness followed, under a dim light casting my lonesome heart.”

A cell in the historic jail at the Tule Lake incarceration camp. The unpainted areas have graffiti.

My family did not arrive in time for the full ranger-led tour, which lasts approximately two hours. Please note that the jail and many areas of the camp are locked and fenced off, and can only be accessed with a park ranger. Ranger guided tours are available between Memorial Day and Labor Day on Thursdays through Sundays and can be booked at least two weeks in advance.

Stepping into the New Visitor Center

In an era when critical race theory is under attack, it is extremely important that the National Park Service has invested in building and operating the Tule Lake Relocation Camp Visitor Center. Currently, the visitor center has temporary exhibits as the NPS gathers public input on what the permanent exhibits should include. So if you have time to visit Tule Lake, be sure to fill out the comment cards and let the NPS know what kinds of exhibits you’d like to see!

Exhibits inside the Tule Lake National Monument visitor center.

The temporary exhibits include a stack of suitcases from the 1940s containing pairs of geta wooden sandals, a Civilian Exclusion Notice from 1942 instructing all persons of Japanese ancestry to pack their belongings and report to a U.S. Army “Reception Center,” and several banner stands with information and photos about topics such as life in the camp, reactions to the loyalty questionnaire, forms of protest within the camp, and more. A computer is available to view digital content, and many information guides and fact sheets are available for visitors to take, which can also be viewed online.

Tips on Visiting Tule Lake

There’s only a month left this year to tour the new visitor center and get a ranger-guided tour. Hopefully some of you can make it!

The Tule Lake National Monument is open Memorial Day through Labor Day, Thursdays through Monday.

See the NPS website for directions and the tour schedule.

Google Maps will navigate you ⅛ mile north of the correct location. If you get lost, park at the locked gate with informational boards (near the jail) and call the visitor center at 530-260-0537.

Reservations are recommended for ranger-guided tours, as only a limited number of people are allowed on each tour.

Besides the visitor center and jail, other locations you can visit include the Tulelake-Butte Valley Fairgrounds Museum, where you can see a guard tower and barrack from the camp, and Camp Tulelake, where some buildings stand.

A free National Park Service app is available with interactive content about Tule Lake.

Check Tule Lake National Monument on Facebook for the latest updates.

Note: If you’d like to see an accurate recreation of an internment camp barrack built by Jimi Yamaichi, visit the Barracks Room at Japanese American Museum of San Jose.

By Michelle Yakura

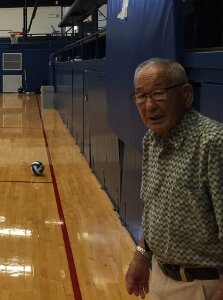

Jimi was a very caring person. This is also true about his wife, Eiko, and the rest of the Yamaichi family. Since Jimi's passing, I have heard numerous stories about how Jimi and Eiko took people under their wing, especially those that lost loved ones or individuals who were new to the community.I remember when I first met Jimi at my first Tule Lake Pilgrimage. I was new in the community and I didn't know anybody as I sat by myself in the auditorium. Jimi came by and sat next to me. He immediately struck up a conversation and gave me some historical items that he had collected. Jimi made me feel very special. Jimi did that with everyone.

Jimi was a very caring person. This is also true about his wife, Eiko, and the rest of the Yamaichi family. Since Jimi's passing, I have heard numerous stories about how Jimi and Eiko took people under their wing, especially those that lost loved ones or individuals who were new to the community.I remember when I first met Jimi at my first Tule Lake Pilgrimage. I was new in the community and I didn't know anybody as I sat by myself in the auditorium. Jimi came by and sat next to me. He immediately struck up a conversation and gave me some historical items that he had collected. Jimi made me feel very special. Jimi did that with everyone. I asked Jimi many questions about the

I asked Jimi many questions about the  One of my last memories of Jimi was at this year's

One of my last memories of Jimi was at this year's  On the day after his passing, it was somewhat difficult for me to give museum tours that day since I always have several Jimi stories that I incorporate into my narrative. I had to pause or slow down a bit after I became a bit emotional. I still get teary-eyed as I tell those stories but I also know that Jimi's spirit, vision, and dreams live on here at the Museum, in San Jose Japantown, at Tule Lake, and most importantly, within all of us.

On the day after his passing, it was somewhat difficult for me to give museum tours that day since I always have several Jimi stories that I incorporate into my narrative. I had to pause or slow down a bit after I became a bit emotional. I still get teary-eyed as I tell those stories but I also know that Jimi's spirit, vision, and dreams live on here at the Museum, in San Jose Japantown, at Tule Lake, and most importantly, within all of us.