The following article was written by JAMsj docent, Will Kaku. He reflects on the Chizuko Judy Sugita de Queiroz’ Camp Days 1942-1945 exhibit. The exhibit will be closing on December 30, 2011.

The Emotional Journey into Camp Days

By Will Kaku

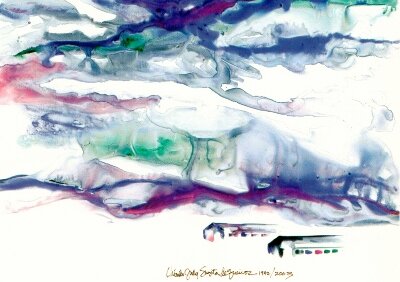

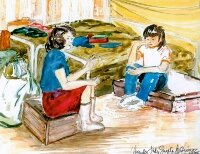

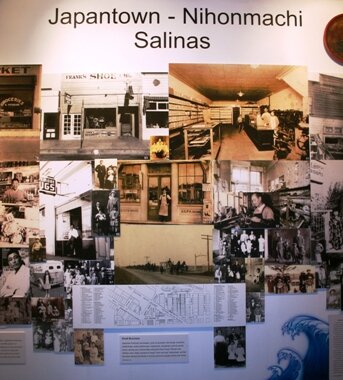

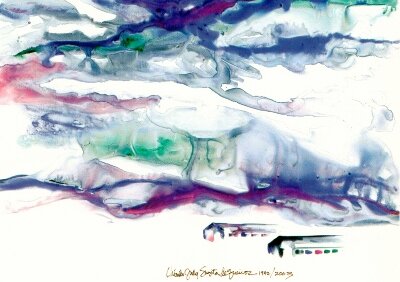

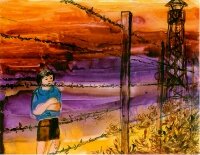

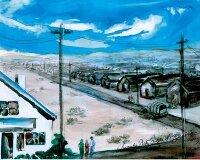

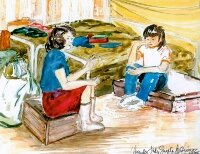

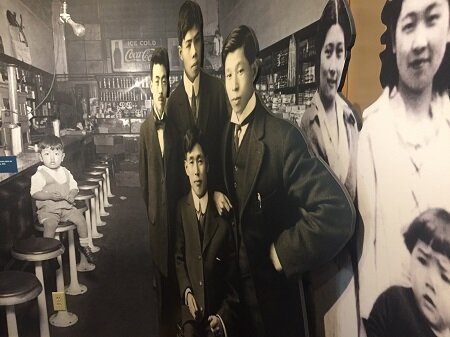

When the JAMsj reopened in October 2010, I used to start my tours like many docents do: in chronological order starting with the story of Chinese and Japanese immigration, the insatiable appetite for cheap labor by agribusiness and industrialists, the impact of racial attitudes and anti-Asian exclusionary laws, and the transition of an immigrant population from a “bachelor society” to one of permanence in San Jose’s Japantown. To me, to start from the beginning was the only way to tell this story.That is how many of us learned history in school. We were often immersed in historical timelines, the identification of key events, influential innovations, political leaders and movements, and the study of causality. There were many facts that had to be understood, necessitating a firm grasp on the “who, what, why, when, and where” of history.When it came to Chizuko Judy Sugita de Quieroz’ watercolor art exhibit, Camp Days 1942-1945, it just didn’t seem to fit my linearly constructed, fact-driven narrative. I often concluded my tours informing my tour group that we also had an art exhibit room which they could walk through and enjoy at their own leisure.I just didn’t get it. I simply saw that there were brightly colored images on the exhibit walls that depicted slices of camp life. There didn’t seem to be any sense of connectivity and profundity, and it missed the opportunity to make an overt political statement. There were also several paintings done in a child-like manner. I could probably paint better than that, I thought.During my breaks, I used to sit and relax in the Camp Days exhibit room, enjoying quiet, introspective times. Letting my mind wander into Chizuko’s paintings, I would reflect on the many former internees that I had met. And eventually, I started to understand.Sometimes the appreciation of art is like that. Like a fine wine, you often can’t appreciate it until you are fully aware of its subtle complexity. You cannot viscerally connect to the work until you are able to unlock the deeply embedded emotional layers. Chizuko’s exhibit describes a young girl’s journey into womanhood and reveals a deeply personal, emotionally scarring reaction to internment, a reaction that many former internees can identify with. For many in the Japanese American community, the repercussions of internment define who we are, shaping our values, political beliefs, and emotional character.In Chizuko’s work, there are basically two major styles represented in the exhibit: a representational form and an abstract form that embeds impressionistic components. Many of the representational forms are painted in a child-like manner, although it would be more accurate to say that they are painted through the eyes of a young Chizuko and layered with the knowledge of what was yet to come from the adult Chizuko.Chizuko had the most difficult time trying to create the abstract forms. Many of these paintings are heavily textured with deep emotions that include sorrow, loneliness, loss, and longing.

When the JAMsj reopened in October 2010, I used to start my tours like many docents do: in chronological order starting with the story of Chinese and Japanese immigration, the insatiable appetite for cheap labor by agribusiness and industrialists, the impact of racial attitudes and anti-Asian exclusionary laws, and the transition of an immigrant population from a “bachelor society” to one of permanence in San Jose’s Japantown. To me, to start from the beginning was the only way to tell this story.That is how many of us learned history in school. We were often immersed in historical timelines, the identification of key events, influential innovations, political leaders and movements, and the study of causality. There were many facts that had to be understood, necessitating a firm grasp on the “who, what, why, when, and where” of history.When it came to Chizuko Judy Sugita de Quieroz’ watercolor art exhibit, Camp Days 1942-1945, it just didn’t seem to fit my linearly constructed, fact-driven narrative. I often concluded my tours informing my tour group that we also had an art exhibit room which they could walk through and enjoy at their own leisure.I just didn’t get it. I simply saw that there were brightly colored images on the exhibit walls that depicted slices of camp life. There didn’t seem to be any sense of connectivity and profundity, and it missed the opportunity to make an overt political statement. There were also several paintings done in a child-like manner. I could probably paint better than that, I thought.During my breaks, I used to sit and relax in the Camp Days exhibit room, enjoying quiet, introspective times. Letting my mind wander into Chizuko’s paintings, I would reflect on the many former internees that I had met. And eventually, I started to understand.Sometimes the appreciation of art is like that. Like a fine wine, you often can’t appreciate it until you are fully aware of its subtle complexity. You cannot viscerally connect to the work until you are able to unlock the deeply embedded emotional layers. Chizuko’s exhibit describes a young girl’s journey into womanhood and reveals a deeply personal, emotionally scarring reaction to internment, a reaction that many former internees can identify with. For many in the Japanese American community, the repercussions of internment define who we are, shaping our values, political beliefs, and emotional character.In Chizuko’s work, there are basically two major styles represented in the exhibit: a representational form and an abstract form that embeds impressionistic components. Many of the representational forms are painted in a child-like manner, although it would be more accurate to say that they are painted through the eyes of a young Chizuko and layered with the knowledge of what was yet to come from the adult Chizuko.Chizuko had the most difficult time trying to create the abstract forms. Many of these paintings are heavily textured with deep emotions that include sorrow, loneliness, loss, and longing.

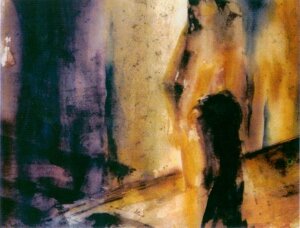

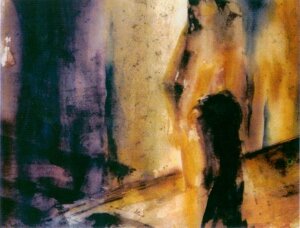

Uncertain Future depicts Chizuko’s family looking far off into the distance, contemplating what their future holds for them when they are finally released from the camp. Many people had great difficulty trying to recover their lives, and some encountered hostile reactions from their former communities. I once met Miyo Uzaki, a former internee, who told me that when she returned to her church in the Fresno area after the war, the pastor of her church informed her that he and the congregation did not want her family to return to the church. JAMsj curator, Jimi Yamaichi, remembered, “When we tried to move into our new home, the neighbors took a vote. We barely got in on a vote of 7 to 6.” Unanswered Prayers covers several major themes that flow throughout Camp Days. In camp, young Chizuko is told that, “If you pray hard enough, your prayers will come true.” Chizuko remarks, “Camp made me realize that my prayers would never be answered. I knew my mother would never come back to life, and I would never be a blue-eyed blond.” This idealized longing for a mother she never knew —she passed away when Chizuko was a baby – is captured in other images in the exhibit. Chizuko states, “Being motherless in camp had a detrimental impact on my childhood. I didn't have anyone. If I had a mother, I'm sure that she would have protected me and taken me every place with her. I wouldn't have had any traumatic experiences”“That painting is an abstract of me,” Chizuko told me. “I’m coming out of the cement shower room, so uncomfortable, sad, and depressed.” The naked body of Chizuko suggests great vulnerability, loneliness, and insecurity. Without her mother, the young Chizuko was becoming increasingly insecure about her body as she moved toward puberty. The lack of privacy in camp also made her feel extremely uncomfortable. Chizuko explained, “I was always embarrassed to shower with a lot of naked women.” In one painting, It’s Not Polite to Stare, she was told that she couldn’t play with her classmates because she had no mother and that she was rude because she stared at another woman in the shower.Her prayer to be non-Japanese in appearance obviously means that she would not have to be in camp if she were a “blue-eyed blond.” But, the wish also carries a deeper implication in the rejection of one’s self. Many of us who grew up in an exclusively Caucasian environment -- in a time when no Asian faces were represented on TV, in films , toys, commercials or magazines -- have harbored similar feelings of “wanting to be white” or a disdain and rejection of everything that was Japanese within ourselves.Other paintings in the exhibit convey similar themes. A Good American, Black and White Houses, Discovery and Disillusionment, and No Japs Allowed, reinforce her feeling of being a “bad person” and reveal her painful reaction to ostracism and discrimination.

Unanswered Prayers covers several major themes that flow throughout Camp Days. In camp, young Chizuko is told that, “If you pray hard enough, your prayers will come true.” Chizuko remarks, “Camp made me realize that my prayers would never be answered. I knew my mother would never come back to life, and I would never be a blue-eyed blond.” This idealized longing for a mother she never knew —she passed away when Chizuko was a baby – is captured in other images in the exhibit. Chizuko states, “Being motherless in camp had a detrimental impact on my childhood. I didn't have anyone. If I had a mother, I'm sure that she would have protected me and taken me every place with her. I wouldn't have had any traumatic experiences”“That painting is an abstract of me,” Chizuko told me. “I’m coming out of the cement shower room, so uncomfortable, sad, and depressed.” The naked body of Chizuko suggests great vulnerability, loneliness, and insecurity. Without her mother, the young Chizuko was becoming increasingly insecure about her body as she moved toward puberty. The lack of privacy in camp also made her feel extremely uncomfortable. Chizuko explained, “I was always embarrassed to shower with a lot of naked women.” In one painting, It’s Not Polite to Stare, she was told that she couldn’t play with her classmates because she had no mother and that she was rude because she stared at another woman in the shower.Her prayer to be non-Japanese in appearance obviously means that she would not have to be in camp if she were a “blue-eyed blond.” But, the wish also carries a deeper implication in the rejection of one’s self. Many of us who grew up in an exclusively Caucasian environment -- in a time when no Asian faces were represented on TV, in films , toys, commercials or magazines -- have harbored similar feelings of “wanting to be white” or a disdain and rejection of everything that was Japanese within ourselves.Other paintings in the exhibit convey similar themes. A Good American, Black and White Houses, Discovery and Disillusionment, and No Japs Allowed, reinforce her feeling of being a “bad person” and reveal her painful reaction to ostracism and discrimination.

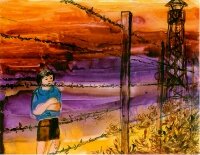

A Good American

Being locked up behind barbed wire, with armed guards, made me feel sad – like maybe I wasn’t a really good American.

|

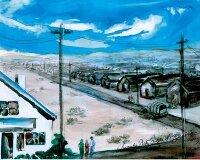

Black and White Houses

Eight year old, Millicent Ogawa, reasoned that, “White people are good so they live in white houses, and we are bad so we live in the black ones.” I thought she was so brilliant. |

Discovery and Disillusionment

I had made a great discovery! I had to tell my sister Lil, “All the people here in camp look Japanese!’ I was the youngest of seven children and no one had told me anything, except that we were just moving. My sister patiently explained racial discrimination to me. I was so depressed. |

When Chizuko speaks about Camp Days, it often leads to tears. Many of her emotions have been bottled up and suppressed over the years. Chizuko suffered great loneliness in camp. Her older siblings told her to just deal with her situation, saying “You’re not a baby anymore.” Much later in life, when she would bring up the topic of camp or her mother, “My brothers and sisters would just say that I just cried and whined all the time and that would end the conversation,” Chizuko explained.Chizuko now says that producing this exhibit was a cathartic experience for her. She normally paints outdoors, but when she painted Camp Days, she isolated herself in a room, revisiting many of the painful memories. All of the emotions that had been previously submerged and invalidated by others could no longer be held back. “I did a lot of gnashing of teeth, crying, laughing, while just remembering more and more details,” Chizuko recalled.The personal, emotional reaction to historical events is one that many people can identify with. During the hearings on redress in the 1980s, many people remember the sudden outpouring of long-held emotions. The emotional repercussions of internment define who many of us are as individuals and as a community. Armed with this deeper knowledge of Camp Days, the life of Chizuko Judy Sugita de Queiroz, and stories from many of the former internees that I have met, I now start rather than end my tours in the Camp Days exhibit. I am very thankful to have taken this emotional journey with Chizuko into Camp Days. This journey will remain with me for a long time.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Some of the Chizuko quotes in this article were taken from the Camp Days film, “Childhood Memories of Chizuko Judy Sugita de Queiros,” produced by Montez Productions. The DVD of this film is available in the JAMsj gift shop.

To get more information from the artist, visit www.artbychiz.com.------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

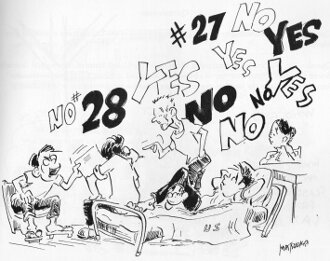

The 39th Annual San Jose Day of Remembrance event commemorates the 77th anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 9066. The order led to the forced removal and incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese descent during World War II. Hundreds of people will gather together at this annual event not only to remember that great civil liberties tragedy but to also reflect on what that event means to all of us today.The 2019 event carries the theme "#Never Again Is Now". During the past year, the story of Japanese American incarceration has been melded into several big national stories.In June, many Americans were alarmed by the consequences of the government's "Zero-Tolerance" border policy. People were horrified when they saw photos of children in cages and when they heard children crying for their parents who were separately held in other detention centers. In an op-ed in the Washington Post, former First Lady Laura Bush wrote, "These images are eerily reminiscent of the Japanese American internment camps in World War II, now considered to have been one of the most shameful episodes in U.S. history."

The 39th Annual San Jose Day of Remembrance event commemorates the 77th anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 9066. The order led to the forced removal and incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese descent during World War II. Hundreds of people will gather together at this annual event not only to remember that great civil liberties tragedy but to also reflect on what that event means to all of us today.The 2019 event carries the theme "#Never Again Is Now". During the past year, the story of Japanese American incarceration has been melded into several big national stories.In June, many Americans were alarmed by the consequences of the government's "Zero-Tolerance" border policy. People were horrified when they saw photos of children in cages and when they heard children crying for their parents who were separately held in other detention centers. In an op-ed in the Washington Post, former First Lady Laura Bush wrote, "These images are eerily reminiscent of the Japanese American internment camps in World War II, now considered to have been one of the most shameful episodes in U.S. history." Other prominent Americans also drew stark parallels with the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. Actor and activist, George Takei, said, "I cannot for a moment imagine what my childhood would have been like had I been thrown into a camp without my parents. That this is happening today fills me with both rage and grief: rage toward a failed political leadership who appear to have lost even their most basic humanity, and a profound grief for the families affected."Another big national story materialized a few weeks later when the United States Supreme Court reversed a series of lower court decisions by upholding the third revision of the Trump travel ban. The decision in Trump v. Hawaii also referred to Japanese American WW II incarceration. Justice Sonia Sotomayor scorching dissent invoked the 1944 Supreme Court case, Korematsu v. United States:

Other prominent Americans also drew stark parallels with the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. Actor and activist, George Takei, said, "I cannot for a moment imagine what my childhood would have been like had I been thrown into a camp without my parents. That this is happening today fills me with both rage and grief: rage toward a failed political leadership who appear to have lost even their most basic humanity, and a profound grief for the families affected."Another big national story materialized a few weeks later when the United States Supreme Court reversed a series of lower court decisions by upholding the third revision of the Trump travel ban. The decision in Trump v. Hawaii also referred to Japanese American WW II incarceration. Justice Sonia Sotomayor scorching dissent invoked the 1944 Supreme Court case, Korematsu v. United States: "By blindly accepting the Government’s misguided invitation to sanction a discriminatory policy motivated by animosity toward a disfavored group, all in the name of a superficial claim of national security, the Court redeploys the same dangerous logic underlying Korematsu and merely replaces one “gravely wrong” decision with another."Although the Court's five majority justices disagreed with Justice Sotomayor, the majority opinion stated that the Court now had the opportunity to "express what is already obvious: Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—has no place in law under the Constitution.”The San Jose Day of Remembrance event was started 39 years ago by local activists to bring awareness of the United States government's actions to forcibly remove and disrupt the Japanese American community. The organizers, the Nihomachi Outreach Committee (NOC), also wanted to use the event to mobilize the community in support of a formal apology by the United States government. This apology was eventually given as a part of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.As recipients of an official apology from the United States government, many Japanese Americans, as well as other Americans, feel that it is their responsibility to defend their friends, neighbors, classmates, colleagues, and other communities when they become the target of discrimination. During these tumultuous and divisive times, ordinary people are rising up within their own communities to effect positive change. This spirit of community activism is captured in the annual San Jose Day of Remembrance event.

"By blindly accepting the Government’s misguided invitation to sanction a discriminatory policy motivated by animosity toward a disfavored group, all in the name of a superficial claim of national security, the Court redeploys the same dangerous logic underlying Korematsu and merely replaces one “gravely wrong” decision with another."Although the Court's five majority justices disagreed with Justice Sotomayor, the majority opinion stated that the Court now had the opportunity to "express what is already obvious: Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—has no place in law under the Constitution.”The San Jose Day of Remembrance event was started 39 years ago by local activists to bring awareness of the United States government's actions to forcibly remove and disrupt the Japanese American community. The organizers, the Nihomachi Outreach Committee (NOC), also wanted to use the event to mobilize the community in support of a formal apology by the United States government. This apology was eventually given as a part of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.As recipients of an official apology from the United States government, many Japanese Americans, as well as other Americans, feel that it is their responsibility to defend their friends, neighbors, classmates, colleagues, and other communities when they become the target of discrimination. During these tumultuous and divisive times, ordinary people are rising up within their own communities to effect positive change. This spirit of community activism is captured in the annual San Jose Day of Remembrance event.

The 39th Day of Remembrance features Don Tamaki, an attorney from the Korematsu Coram Nobis legal team; Teresa Castellanos, a representative from the County of Santa Clara Office of Immigrant Relations; Chizu Omori, an activist, former internee, and co-producer of the film, "Rabbit in the Moon"; a special performance by internationally acclaimed San Jose Taiko, and the traditional candlelight procession through historic San Jose Japantown.

The 39th Day of Remembrance features Don Tamaki, an attorney from the Korematsu Coram Nobis legal team; Teresa Castellanos, a representative from the County of Santa Clara Office of Immigrant Relations; Chizu Omori, an activist, former internee, and co-producer of the film, "Rabbit in the Moon"; a special performance by internationally acclaimed San Jose Taiko, and the traditional candlelight procession through historic San Jose Japantown.

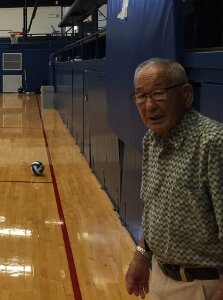

Jimi was a very caring person. This is also true about his wife, Eiko, and the rest of the Yamaichi family. Since Jimi's passing, I have heard numerous stories about how Jimi and Eiko took people under their wing, especially those that lost loved ones or individuals who were new to the community.I remember when I first met Jimi at my first Tule Lake Pilgrimage. I was new in the community and I didn't know anybody as I sat by myself in the auditorium. Jimi came by and sat next to me. He immediately struck up a conversation and gave me some historical items that he had collected. Jimi made me feel very special. Jimi did that with everyone.

Jimi was a very caring person. This is also true about his wife, Eiko, and the rest of the Yamaichi family. Since Jimi's passing, I have heard numerous stories about how Jimi and Eiko took people under their wing, especially those that lost loved ones or individuals who were new to the community.I remember when I first met Jimi at my first Tule Lake Pilgrimage. I was new in the community and I didn't know anybody as I sat by myself in the auditorium. Jimi came by and sat next to me. He immediately struck up a conversation and gave me some historical items that he had collected. Jimi made me feel very special. Jimi did that with everyone. I asked Jimi many questions about the

I asked Jimi many questions about the  One of my last memories of Jimi was at this year's

One of my last memories of Jimi was at this year's  On the day after his passing, it was somewhat difficult for me to give museum tours that day since I always have several Jimi stories that I incorporate into my narrative. I had to pause or slow down a bit after I became a bit emotional. I still get teary-eyed as I tell those stories but I also know that Jimi's spirit, vision, and dreams live on here at the Museum, in San Jose Japantown, at Tule Lake, and most importantly, within all of us.

On the day after his passing, it was somewhat difficult for me to give museum tours that day since I always have several Jimi stories that I incorporate into my narrative. I had to pause or slow down a bit after I became a bit emotional. I still get teary-eyed as I tell those stories but I also know that Jimi's spirit, vision, and dreams live on here at the Museum, in San Jose Japantown, at Tule Lake, and most importantly, within all of us.

By Will KakuThe Heart Mountain

By Will KakuThe Heart Mountain  Despite that significance in my family’s history, I could never find the time to make the journey to the

Despite that significance in my family’s history, I could never find the time to make the journey to the  The Heart Mountain Interpretative Center opened in 2011, just a year after we completed the major renovation of JAMsj. Because I assisted in providing content for the JAMsj camp exhibit, I was fully aware of space, cost, and vision constraints that had to be considered in exhibit design. I was keenly interested in how the

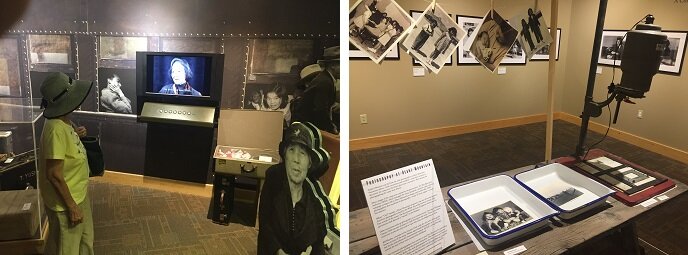

The Heart Mountain Interpretative Center opened in 2011, just a year after we completed the major renovation of JAMsj. Because I assisted in providing content for the JAMsj camp exhibit, I was fully aware of space, cost, and vision constraints that had to be considered in exhibit design. I was keenly interested in how the  One major aspect of the HWMF presentation, the first-person narrative, is extremely effective in bringing out an emotional connection to an infamous event in our nation’s history from over 75 years ago. After a short museum overview, my mom and I were encouraged to view the short film, All We Could Carry, by Oscar-winning filmmaker, Steven Okazaki. All We Could Carry powerfully captures the devastating impact of incarceration at Heart Mountain through the voices of former inmates.

One major aspect of the HWMF presentation, the first-person narrative, is extremely effective in bringing out an emotional connection to an infamous event in our nation’s history from over 75 years ago. After a short museum overview, my mom and I were encouraged to view the short film, All We Could Carry, by Oscar-winning filmmaker, Steven Okazaki. All We Could Carry powerfully captures the devastating impact of incarceration at Heart Mountain through the voices of former inmates.

Several kiosks in the museum also incorporate moving first-person accounts. Exhibit placards continuously reinforce the first-person point of view by utilizing the inclusive pronoun "we". We felt that we were also making our own journey through the great civil liberties and human rights tragedy from WW II.

Several kiosks in the museum also incorporate moving first-person accounts. Exhibit placards continuously reinforce the first-person point of view by utilizing the inclusive pronoun "we". We felt that we were also making our own journey through the great civil liberties and human rights tragedy from WW II. The 11,000 square feet of space also enables exhibit images and artifacts to extend out into the floor space, providing a fully immersive experience to the visitor.

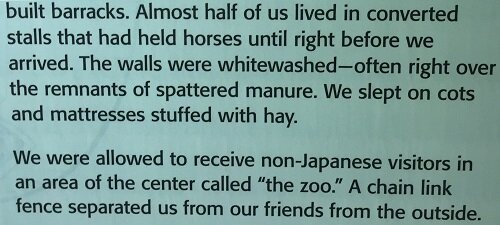

The 11,000 square feet of space also enables exhibit images and artifacts to extend out into the floor space, providing a fully immersive experience to the visitor. Every square foot of the museum is used to transport you back into the diverse and complex Japanese American incarceration experience. Even the reflective restroom toilet stalls convey the feeling of embarrassment and the loss of privacy that many former inmates experienced in the camps.

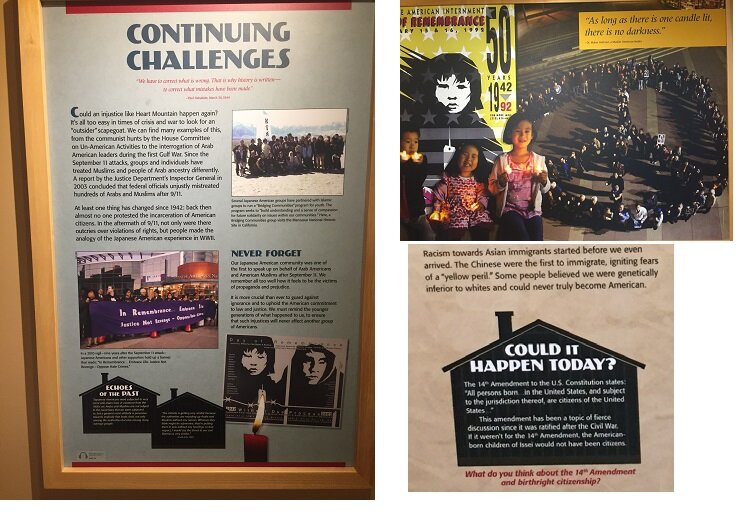

Every square foot of the museum is used to transport you back into the diverse and complex Japanese American incarceration experience. Even the reflective restroom toilet stalls convey the feeling of embarrassment and the loss of privacy that many former inmates experienced in the camps. Importantly, the museum exhibits challenge visitors with questions that are pertinent to our lives and political discourse today. One display asks us about what we think about the 14th Amendment and birthright citizenship. Another asks us if there are any circumstances under which the curtailment of civil liberties by the government is justified.

Importantly, the museum exhibits challenge visitors with questions that are pertinent to our lives and political discourse today. One display asks us about what we think about the 14th Amendment and birthright citizenship. Another asks us if there are any circumstances under which the curtailment of civil liberties by the government is justified. It took us a long time to explore the many museum displays and my mother became tired. We came back the next morning and wandered around the self-guided walking tour next to the museum. We saw the locations of the Heart Mountain hospital where my father worked for a short time, the school that he attended, and the train station where my father boarded a train that transferred him to the Tule Lake camp. We walked solemnly during that quiet, cool morning and we reflected on his life.

It took us a long time to explore the many museum displays and my mother became tired. We came back the next morning and wandered around the self-guided walking tour next to the museum. We saw the locations of the Heart Mountain hospital where my father worked for a short time, the school that he attended, and the train station where my father boarded a train that transferred him to the Tule Lake camp. We walked solemnly during that quiet, cool morning and we reflected on his life.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Related articles by Will Kaku:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Related articles by Will Kaku: