On June 12, 2011, former Japanese American internees and their families joined with Holocaust survivors to share their life stories at the third Gathering of Friends event held at the Japanese American Museum of San Jose. Harvey Gotliffe, one of the program organizers, talks about what inspired him to create this unique and special event.

Why have a Gathering of Friends?

By Harvey Gotliffe

In 1972, while teaching at Fresno State, I listened to the internment story of my graduate assistant and friend Sam Masumoto and his family, who gave me a copy of Boswell’s book America’s Concentration Camps. I continued to learn about the internment and in 2000, as a San Jose State University journalism professor, I introduced a class entitled “How the American Media Covered the Japanese American Internment and the Holocaust during World War Two.” Holocaust survivors came in and told their stories to the class as did former Japanese American internees including Jimi and Eiko Yamaichi, Katsumi and Alice Hikido, and author Jeanne Houston. Each semester, several former internees volunteered to be interviewed in their homes by only two to three students at a time, allowing living history to be told and passed on.

In 1972, while teaching at Fresno State, I listened to the internment story of my graduate assistant and friend Sam Masumoto and his family, who gave me a copy of Boswell’s book America’s Concentration Camps. I continued to learn about the internment and in 2000, as a San Jose State University journalism professor, I introduced a class entitled “How the American Media Covered the Japanese American Internment and the Holocaust during World War Two.” Holocaust survivors came in and told their stories to the class as did former Japanese American internees including Jimi and Eiko Yamaichi, Katsumi and Alice Hikido, and author Jeanne Houston. Each semester, several former internees volunteered to be interviewed in their homes by only two to three students at a time, allowing living history to be told and passed on. I became friends with many former internees and Holocaust survivors, saw the serendipitous relationship between members of both groups and noted that they had much in common. The commonality includes strong family ties, high moral values, contributions to the community, and working in their own way to help ensure that the wrongs that befell them do not happen again. Many from each group regularly speak to students in classrooms to provide living history experiences, to educate the young about the past, and to instill in them what they can do to make the world a better place to live in.Both groups suffered gross injustices during World War Two, and I thought that it would be an exceptionally stimulating experience for members of each group to get together at a Gathering of Friends. In 2005 they shared lunch and sat together and talked about their experiences before, during and since the war ended. It was a time to share and not to compare, and it had a most successful beginning at the Japanese American Museum, followed by a 2008 Gathering at the Chai House in San Jose, and now the Third Gathering of Friends at JAMsj has added to the understanding and the friendships.Harvey Gotliffe’s writings can be found on his blog at http://theho-ho-kuscogitator.blogspot.com/ and on the Huffington Post at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/harvey-gotliffe-phd/

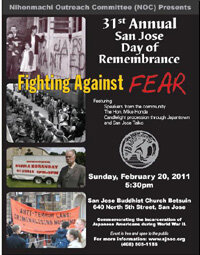

I became friends with many former internees and Holocaust survivors, saw the serendipitous relationship between members of both groups and noted that they had much in common. The commonality includes strong family ties, high moral values, contributions to the community, and working in their own way to help ensure that the wrongs that befell them do not happen again. Many from each group regularly speak to students in classrooms to provide living history experiences, to educate the young about the past, and to instill in them what they can do to make the world a better place to live in.Both groups suffered gross injustices during World War Two, and I thought that it would be an exceptionally stimulating experience for members of each group to get together at a Gathering of Friends. In 2005 they shared lunch and sat together and talked about their experiences before, during and since the war ended. It was a time to share and not to compare, and it had a most successful beginning at the Japanese American Museum, followed by a 2008 Gathering at the Chai House in San Jose, and now the Third Gathering of Friends at JAMsj has added to the understanding and the friendships.Harvey Gotliffe’s writings can be found on his blog at http://theho-ho-kuscogitator.blogspot.com/ and on the Huffington Post at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/harvey-gotliffe-phd/